Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap and Others Don't by Jim Collins

A summary and review of Jim Collin's book, Good to Great.

“Jeff [Bezos] and the S-Team were reading…Good to Great. And you have to ask Jeff what it is, but if you ask me, I think that this was the single most influential and effective management book for [Amazon] because what it caused Jeff to do…It is, in my opinion, the best, most important management book you'll ever read.” — Bill Carr, co-author of Working Backwards and founder of Prime Video, Amazon Studios and Amazon Music

Truly great companies, for the most part, have always been great. And the vast majority of good companies never become great.

We don't have more great companies precisely because most companies become quite good. Good is the enemy of great.

But the transition from good to great does happen, but how does it happen?

To find out, Jim and his team identified companies that made the leap from good results to great results for at least fifteen years. They compared these companies to a group of comparison companies that failed to make or sustain the leap, then they looked for the distinguishing factors.

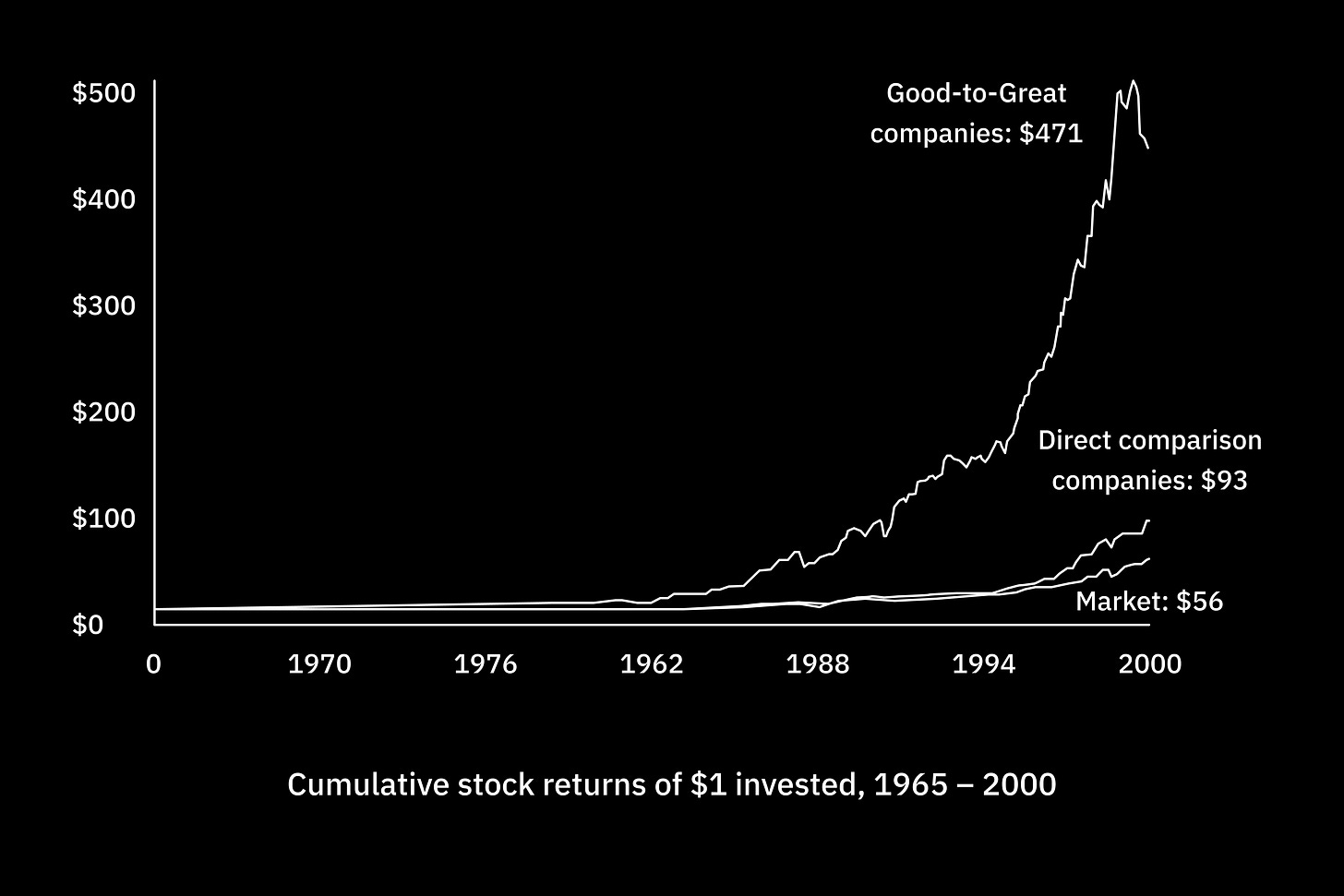

The good-to-great companies averaged cumulative stock returns 6.9 times the general stock market in the fifteen years following their transition points. To put that into perspective, every dollar invested into a fund of the good-to-great companies in 1965 that was held until January 1, 2000 would have multiplied 471 times, compared to a 56 fold increase in the market.

These are remarkable numbers, made more remarkable when you consider that many of these companies had been utterly unremarkable before their transition.

The search

Jim and his team looked for companies with fifteen-year cumulative stock returns at or below the general stock market, punctuated by a transition point, then cumulative returns at least three times the market over the next fifteen years.

Fifteen years was long enough to avoid one-hit wonders and lucky breaks, and is longer than the tenure of most chief executive officers. This helps separate great companies from companies that happened to have a single great leader. And three times the market exceeded the performance of most widely recognized great companies between 1985 and 2000, think companies like Coca-Cola, Intel, Wal-Mart, and Disney.

Good-to-great companies also had to demonstrate the good-to-great pattern independent of their industry, if the industry showed the same pattern, they dropped the company.

The final set of companies is as follows:

Compared to what?

Next they contrasted the good-to-great companies with comparison companies to determine what differentiated them.

There were two sets of comparison companies. The first were direct comparisons. Companies in the same industry with the same opportunities and similar resources at the time of transition that showed no change in performance.

The second were unsustained comparisons. Companies that made a short-term shift from good to great but failed to maintain the trajectory.

This produced a list of twenty-eight companies: eleven good-to-great companies, eleven direct comparisons, and six unsustained comparisons.

Inside the black box

Then they collected all articles published on the twenty-eight companies, dating back fifty years or more, coded all the material into categories, interviewed most of the good-to-great executives who held key positions during the transition, and performed a wide range of qualitative and quantitative analysis.

The core of their method was to contrast the good-to-great companies to the comparisons. Think of their research as akin to looking inside a black box, each step shed more light on the good-to-great process.

What they didn't find turned out to be some of the most important findings.

Larger-than life leaders who came from the outside were negatively correlated with taking a company from good to great. Ten of the 11 good-to-great CEOs came from within. Executive compensation didn't matter.

Strategy did not separate the good-to-great companies from the comparisons. Both sets had well-defined strategies.

The good-to-great companies didn't focus on what to do, rather what not to do and what to stop doing. Technology accelerated but did not cause transformations. Mergers and acquisitions played no role in transforming from good-to-great.

Good-to-great companies paid little attention to managing change, motivating people, or creating alignment.

There was no single event that signified the transformation from good-to-great. Some even reported being unaware of the magnitude of the transformation at the time, and many good-to-great companies were not in great industries and some were in terrible industries.

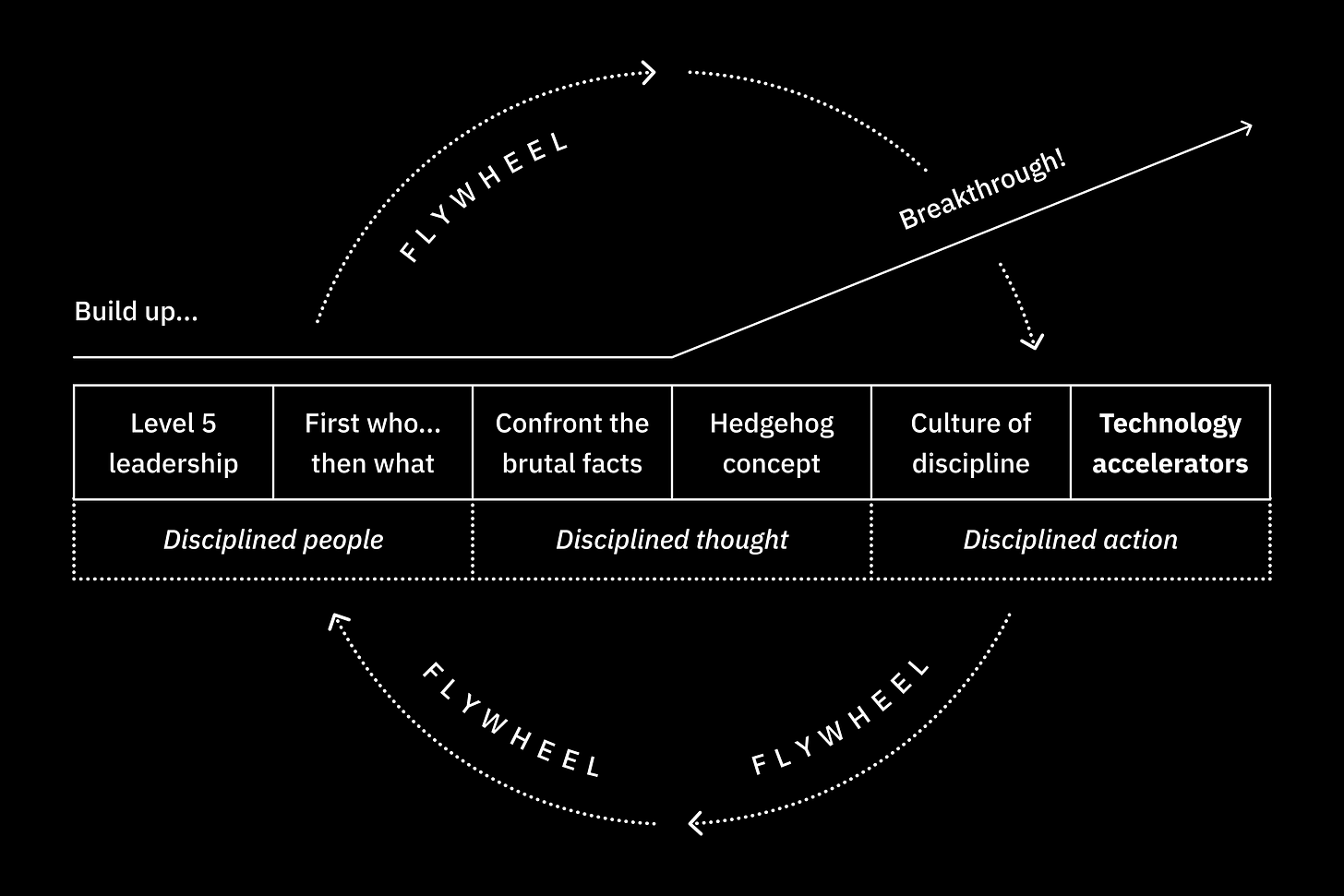

Chaos to concept

Now let's go over the framework of concepts and preview what is to come. Think of the transformation as a process of buildup followed by breakthrough, broken into three stages: disciplined people, disciplined thought, and disciplined action.

Each stage has two key concepts and wrapping the entire framework is the flywheel which captures the entire process of going from good to great. Good-to-great transformations never happened in one fell swoop. Rather it resembles pushing a giant heavy flywheel in one direction, building momentum, until a point of breakthrough.

Level 5 Leadership: Good-to-great leaders tend to be self-effacing, quiet, reserved, and even shy. A paradoxical blend of personal humility and professional will.

First Who...Then What: Get the right people on the bus, the wrong people off the bus, the right people in the right seats then figure out where to go.

Confront the Brutal Facts (Yet Never Lose Faith): Every good-to-great company embraced the Stockdale Paradox. Unwavering faith that you can and will prevail regardless of difficulty while having the disciple to confront reality, whatever it may be.

The Hedgehog Concept (Simplicity within the Three Circles): Going from good to great means transcending the curse of competence. If you can't be the best in the world at it, it can't form the basis of a great company.

A Culture of Discipline: When you have disciplined people, you don't need hierarchy, bureaucracy, or excessive controls.

Technology Accelerators: Technology alone cannot transform a company from good to great, but good-to-great companies were pioneers in the application of carefully selected technologies.

Each of these concepts showed up as a change variable in 100 percent of the good-to-great companies and in less than 30 percent of the comparison companies.

The timeless "physics" of good to great

Good to great isn't about specific companies or timeframes, it's about identifying principles–the enduring physics of great organizations–that remain true and relevant no matter how the world changes around us. Specific applications will change but the principles will endure.

It's about how to take a good organization and turn it into one that procedures sustained great results, using whatever definition of results best applies to your organization.

Good being the enemy of great is not a business problem. It's a human problem. If we can understand what turns good into great, we have something of value for any organization.

Level 5 leadership

Every good-to-great company had a Level 5 leader. Furthermore, the absence of Level 5 leadership was a consistent pattern in the comparison companies.

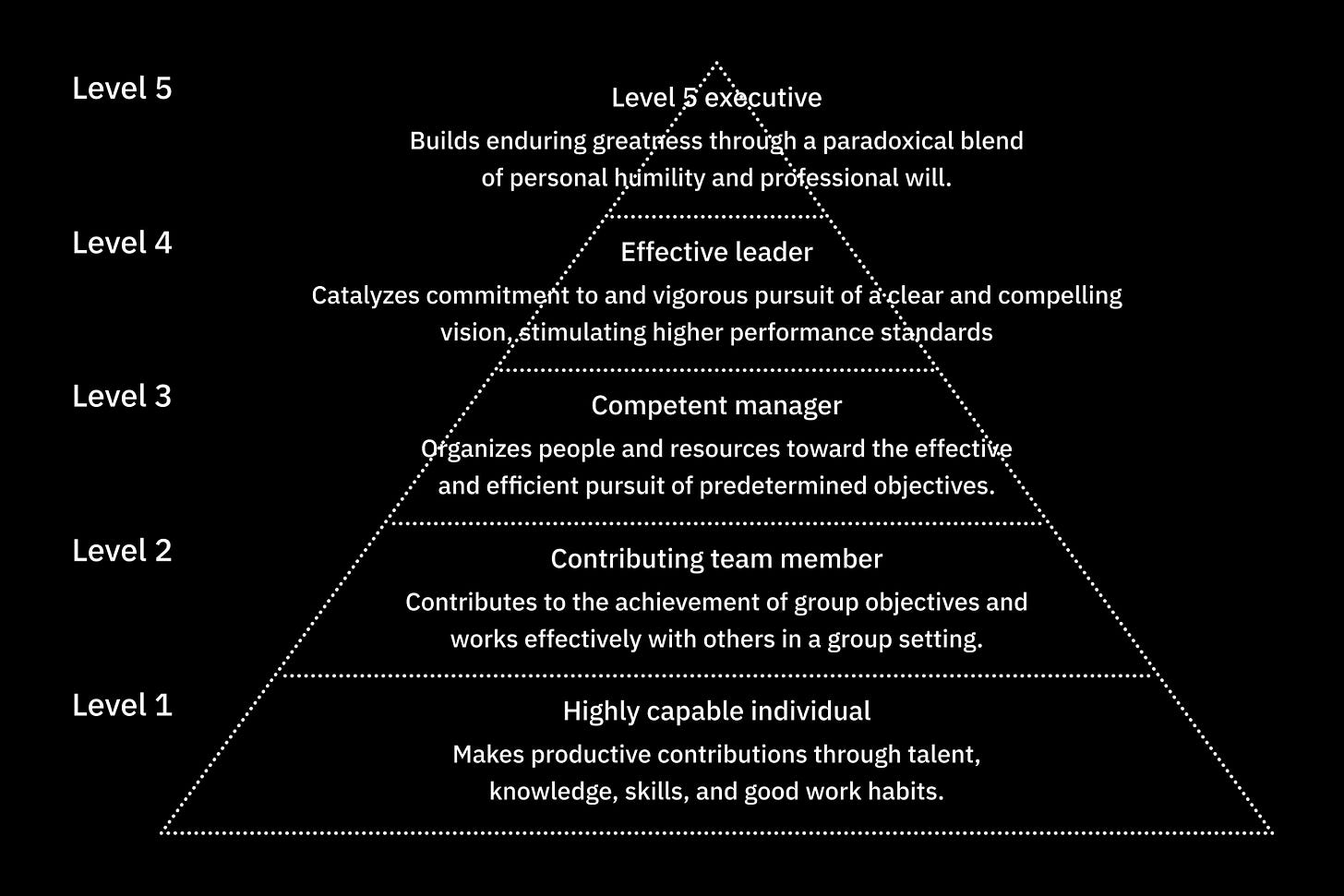

Level 5 refers to a five-level hierarchy of executive capabilities:

Level 1: A highly capable individual who makes productive contributions through talent, knowledge, skills, and good work habits

Level 2: A contributing team member who contributes individual capabilities to the achievement of group objectives and works effectively with others in a group setting

Level 3: A competent manager who organizes people and resources toward the effective and efficient pursuit of predetermined objectives

Level 4: An effective leader catalyzes commitment to and vigorous pursuit of a clear and compelling vision, stimulating higher performance standards

Level 5: A level 5 executive builds enduring greatness through a paradoxical blend of personal humility and professional will.

They're incredibly ambitious, but the ambition is first and foremost for the cause, not themselves.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, Level 5 leaders are often self-effacing, quiet, reversed, even shy. More likely to motivate with inspired standards than inspiring personality.

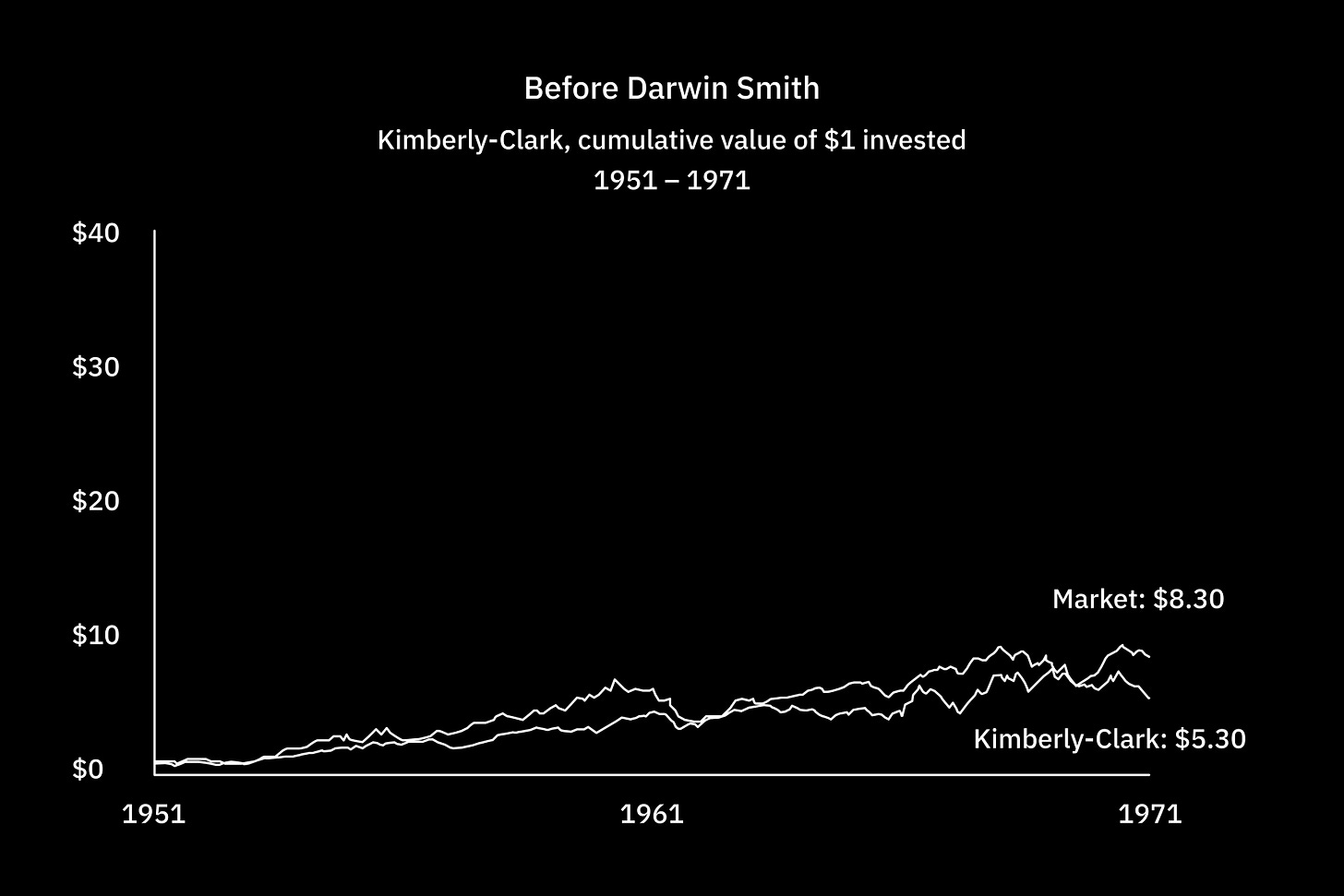

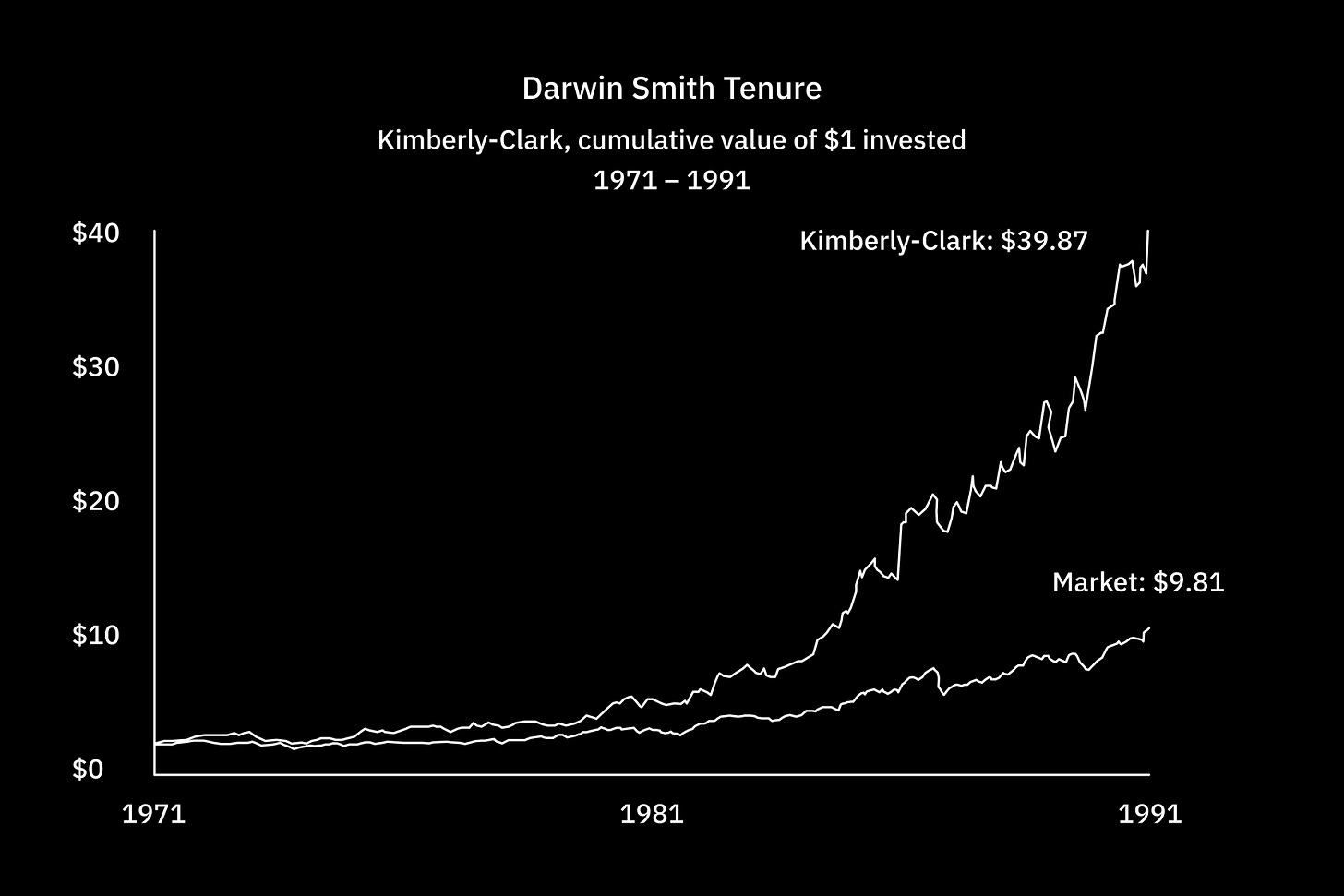

One such leader was Darwin E. Smith who became chief executive of Kimberley-Clark, a paper company whose stock had fallen 36 percent behind the general market over the previous 20 years.

Smith, the company's mild-manner lawyer, wasn't sure the board made the right decision which was reinforced when a director reminded him that he lacked qualifications.

But over the next twenty years, Smith transformed Kimberley-Clark, generating cumulative stock returns 4.1 times the general market.

Yet few people know anything about Darwin Smith, and he probably would have liked that.

In retirement, Smith reflected on his exceptional performance, stating "I never stopped trying to become qualified for the job."

Not what is expected

Jim gave his research teams explicit instructions to downplay the role of leadership to avoid the simplistic "credit or blame the leader" thinking that is prevalent today.

To use analogy, the "Leadership is the answer to everything" perspective is equivalent to "God is the answer to everything" that held back scientific understanding of the physical world. If we attribute everything to "Leadership", we prevent ourselves from gaining a deeper understanding of what makes great companies tick.

The comparison companies also had leaders, so how could leadership be a differentiator?

Because a Level 5 leader was at the helm of every good-to-great company during their transition.

Furthermore, the absence of Level 5 leadership was a consistent pattern in the comparison companies.

Given Level 5 leadership goes against the conventional wisdom of needing larger-than-life leaders to transform companies, it's important to note Level 5 is an empirical, not ideological, finding.

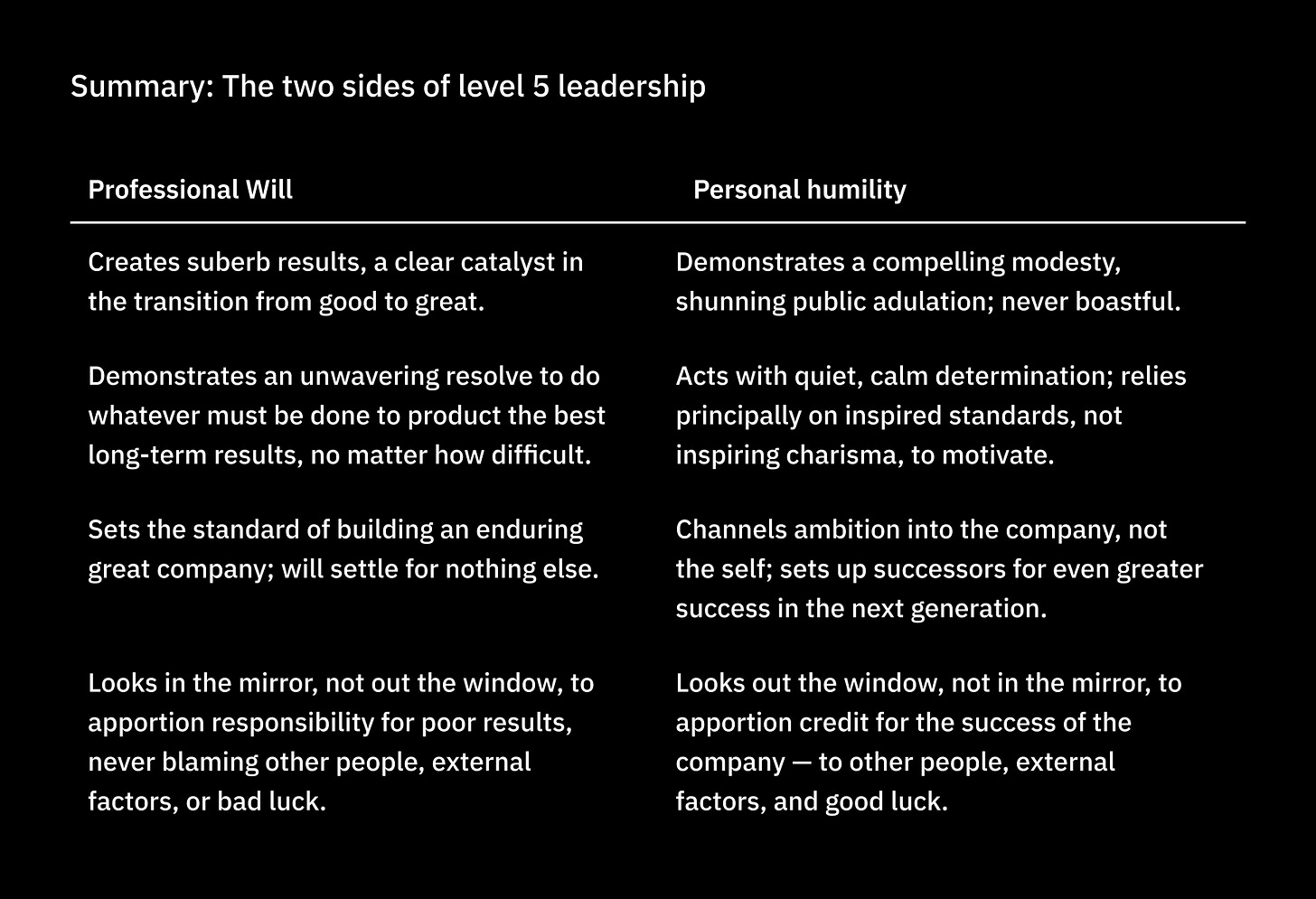

Humility + will = level 5

Level 5 leaders are a study of duality: modest and willful, humble and fearless.

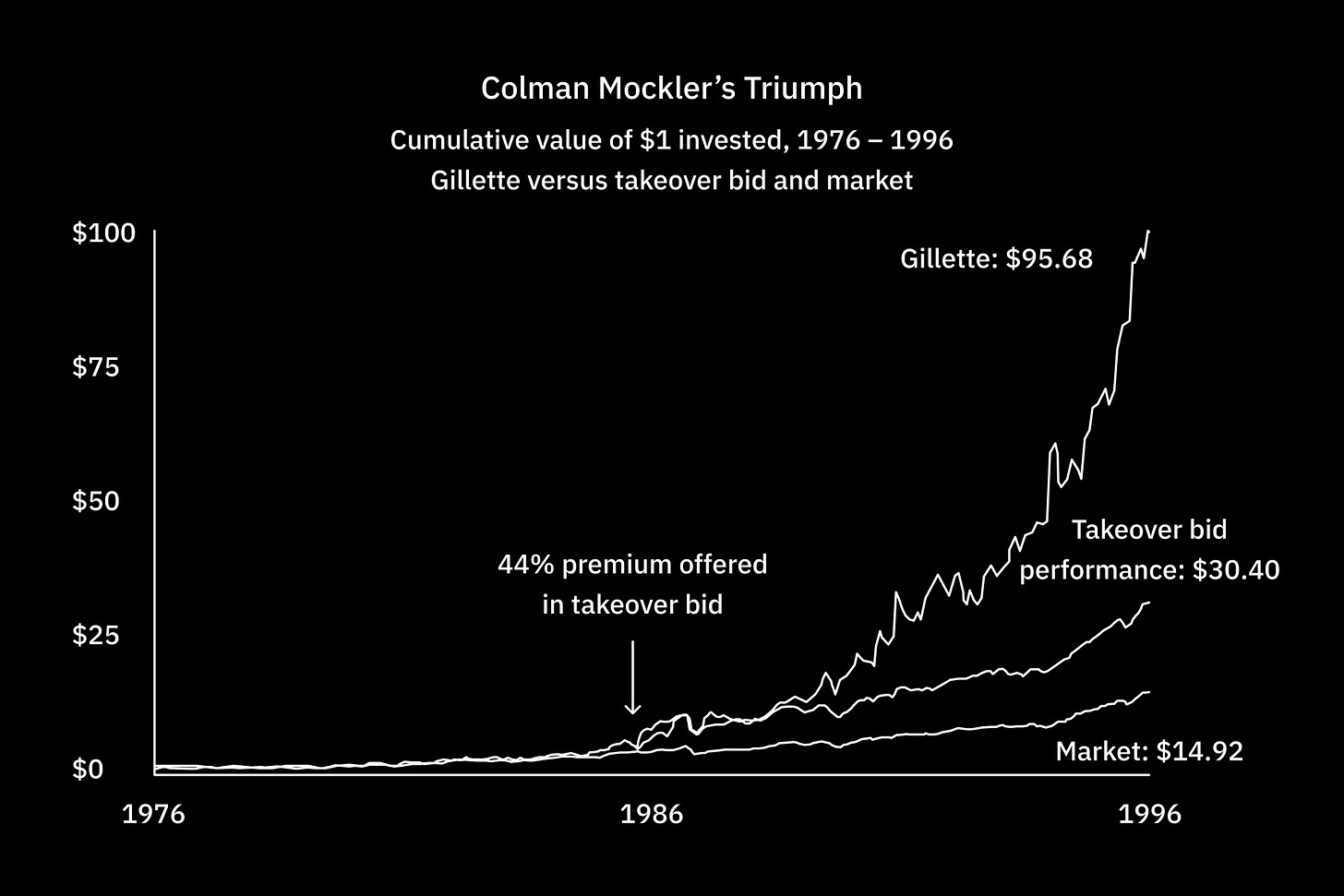

Consider Colman Mockler, CEO of Gillette from 1975 to 1991. During Mockler's tenure, Gillette faced three attacks that threatened to destroy their chance at greatness.

Two attacks came as hostile takeover bids from Revlon, led by Ronald Perelman. The third came from Coniston Partners, who bought 5.9 percent of Gillette stock and initiated a proxy battle to seize control of the company in hopes of selling it to the highest bidder.

Had Mockler accepted Perelman's offer, shareholders would have reaped an instant 44 percent gain on their stock.

Most executives would have cashed in, but Mockler and Gillette's executives instead chose to fight reaching out to thousands of individual investors to win the battle.

Mockler and his team were staking the company's future on huge investments into Sensor and Mach3, had the takeover been successful these projects would have almost certainly been eliminated.

These investments promised significant future profits that weren't reflected in the stock price because of their secrecy.

The board and Mockler believed the future value of the shares far exceeded the current price, even with the price premium offered, and they were right. To sell out would have made short-term investors happy but would have been terrible for long-term shareholders.

If Mockler had accepted the 44 percent price premium offered on October 31, 1986 and then people invested the full amount in the general stock market for ten years to the end of 1996, they would have come out three times worse off than a shareholder who stayed with Mockler and Gillette.

Setting up successors for success

Level 5 leaders want to see the company even more successful in the next generation. They're comfortable with the idea that most people won't even know that the roots of the success trace back to their efforts.

In contrast, the comparison leaders were more concerned with their own reputation. Over three quarters of the comparison company leaders failed to set up their successors for success, chose a weak successor, or both.

While some of the comparisons took their companies from good to great for a brief moment, when they left, the company went from great to irrelevant.

After all, what better testament to your own personal greatness than a place that falls over after you leave?

Compelling modesty

In contrast to the I-centric style of the comparison leaders, good-to-great leaders didn't talk about themselves. They talked about the company and the contributions other executives made, avoiding discussions about their own accomplishments.

It wasn't false modesty. Those who worked or wrote about good-to-great leaders frequently used words like quiet, humble, modest, reserved, shy, gracious, mild-mannered, self-effacing, and understated.

The eleven good-to-great CEOs were some of the most remarkable CEOs of the century yet almost no one ever remarked about them. They never wanted to be larger-than-life heroes. They were ordinary people quietly producing extraordinary results.

In contrast, two thirds of the comparison companies had an egocentric leader that contributed to the demise or continued mediocrity of the company.

This pattern was particularly strong in the unsustained comparisons–cases where the company would show a leap in performance under a talented leader, only to decline in later years.

Unwavering resolve to do what must be done

Level 5 leadership is not just about humility and modesty. It's equally about the resolve to do what needs to be done.

They're fanatically driven to produce results, displaying workman like diligence–more plow horse than show horse.

George Cain, who became CEO of Abbott Laboratories after working there for eighteen years, is one example. He couldn't stand mediocrity and was intolerant of anyone who would accept the idea that good was good enough.

He set out to destroy one of the key causes of Abbott's mediocrity: nepotism. Systematically rebuilding the board and executive team with the best people he could find.

If you didn't have the capability to be the best executive in the industry, you were out.

This is something you'd expect from an outsider brought in to turn the company around, but Cain was an insider. In fact, he was a family member, the son of a previous Abbott president.

Even if they got fired, family members had to be pleased with the performance of their stock. Cain set in motion a profitable growth machine that beat the market by 4.5 times between 1974 and 2000.

This reflects a more systematic finding of Good to Great. Evidence did not support the idea that you need an outside leader to go from good to great. In fact, high profile outsiders were negatively correlated with a sustained transformation.

Ten out of the eleven good-to-great CEOs came from inside the company, three of them by family inheritance. The comparison companies turned to outsiders six times often — yet they failed to produce sustained great results.

The window and the mirror

The good-to-great executives talked a lot about luck. Some even flat-out refused to take credit for their company's success, attributing it to the good fortune of having great colleagues, successors, and predecessors.

At first, Jim and his team were puzzled by this emphasis on luck. They found no evidence that the good-to-great companies were blessed with more good luck than the comparison companies.

Then they noticed a contrasting pattern in the comparison executives. They credited substantial blame to bad luck.

The emphasis on luck turns out to be part of a pattern called the window and the mirror.

Level 5 leaders look out the window and attribute success to factors other than themselves. When things go poorly, they look in the mirror and blame themselves, taking full responsibility.

The comparison CEOs did the opposite, looking in the mirror to take credit and out the window to assign blame.

Cultivating level 5 leadership

Jim's hypothesis is there are two types of people: those who have the seed of Level 5, and those who don't. For those who don't, work will always be about what they get, not what they build.

The great irony is personal ambition often drives people toward positions of power but stands at odds with the humility required for Level 5 leadership.

Most people have the seed of Level 5. The problem is not a dearth of potential Level 5 leaders. Rather it's the fact that people operate under the belief that you need to hire larger-than-life leaders to make an organization great, this is why Level 5 leaders rarely appear as CEOs.

To find Level 5 leaders, look for places where extraordinary results exist but no individual steps forward to claim credit.

For your own development, begin practicing the other good-to-great concepts. This is about what Level 5s are, the remaining concepts cover what they do.

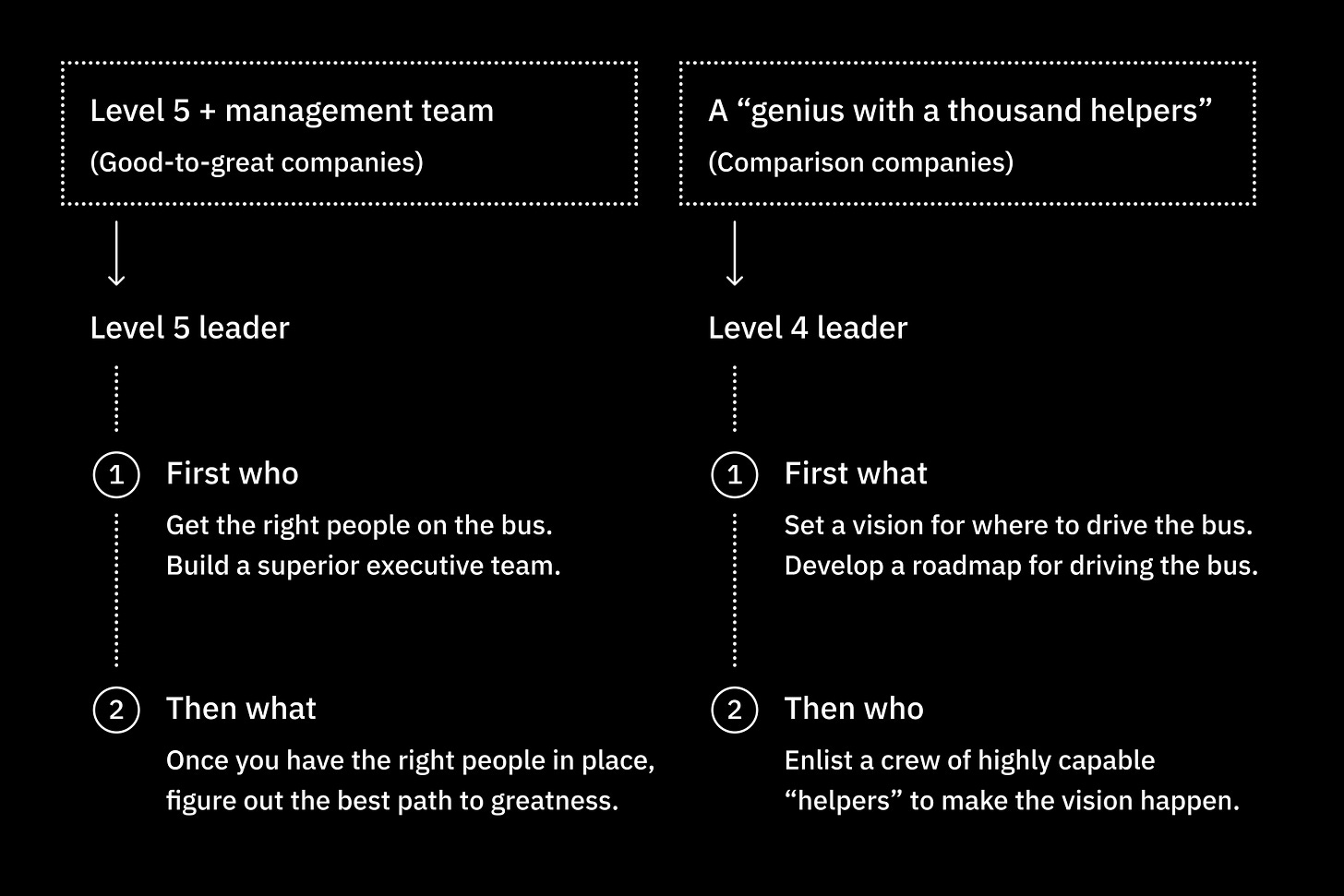

First Who...Then What

You'd think the first step in taking a company from good to great would be to set a new direction and get people committed to it.

The opposite is closer to the truth. The transformation begins by getting the right people on the bus, the wrong people off the bus, then you figure out where to go.

The key point is not just the idea of getting the right people on the team. It's about answering the who question before making the what decisions. First who, then what.

Starting with who, rather than what, means you can more easily adapt to change.

If people join because of where you're going, you're going to have problems if you need to change course. But if people are on the bus because of who else is there, it's going to be easier to change direction.

When you have the right people, problems with motivation and management largely go away. The right people have an inner drive to produce the best results and to be part of something great.

If you have the wrong people, it doesn't matter whether you find the right direction; you still won't have a great company.

Great vision, without great people, is irrelevant.

First who...then what is a simple idea to grasp, but hard to do in practice–and most don't do it well.

Not a genius with a thousand helpers

In contrast to the good-to-great companies, the comparison companies followed a genius with a thousand helpers model. They were platforms for an extraordinary individual to set their vision and enlisted a crew of highly capable helpers to make the vision real.

Having a single driving force for a company's success is a great asset–as long as the genius sticks around. The issue is these geniuses seldom build great management teams, for the simple reason that they didn't need, or often, want one.

When the genius leaves, the helpers are often lost. Or, worse, they try to mimic their predecessor with bold, visionary moves–trying to act like a genius, without being one.

It's who you pay, not how you pay them

You'd expect that changes in incentives would be correlated with making the leap from good to great, but compensation played no part.

Not that executive compensation is irrelevant. You need to be reasonable, but once you've got something that makes sense, compensation falls away as a distinguishing factor.

Compensation isn't about motivating the right behaviors from the wrong people, it's how you get and keep the right people in the first place.

It's who you compensate, not how you compensate them that's important.

If you have the right people, they'll do everything they can to build a great company. Not because of what they'll get, but because they can't settle for less.

The right people do the right things and deliver the best results they're capable of, regardless of incentive.

And whether someone is the right person has more to do with character traits and innate capabilities than specific knowledge, background, or skill. Not that these are unimportant, but these traits are teachable while character traits, work ethic, dedication to commitments, and values are more ingrained.

Rigorous, not ruthless

Good-to-great leaders are rigorous, but not ruthless, in people decisions.

Ruthless means using layoffs and restructuring, especially during difficult times, as the primary strategy for improving performance. The evidence suggests such tactics are contrary to producing sustained great results.

Six of the eleven good-to-great companies recorded zero layoffs from ten years before their breakthrough date all the way through 1998, and four others reported only one or two layoffs. In contrast, layoffs were used five times more frequently in the comparison companies.

Some had an almost chronic addiction to layoffs and restructuring.

Rigorous means consistently applying exacting standards at all times and at all levels, especially in upper management. Rigor applies first at the top, focused on those who hold the burden of responsibility.

How to be rigorous

There are three disciplines you need to follow to be rigorous:

When in doubt, don't hire–keep looking

When you know you need to make a people change, act

Put your best people on your biggest opportunities, not your biggest problems

1. When in doubt, don't hire–keep looking

One of the immutable laws of management physics is Packard's Law: No business can grow revenues consistently faster than its ability to get enough of the right people to implement that growth and still become a great company.

If your revenue growth consistently outpaces your ability to get and retain the right people, you can’t build a great company.

Those who build great companies understand the ultimate throttle on growth isn't the market, technology, competition, or products. It's people.

Limit growth based on your ability to attract enough of the right people.

2. When you know you need to make a people change, act

Good-to-great companies showed a bipolar pattern at the top management level: People either stayed for a long time or got off in a hurry.

Letting the wrong people hang around is unfair to the right people as they'll have to compensate for their inadequacies. Worse, it drives away the best people.

Waiting too long before acting is equally unfair to those who need to get off the bus. Every minute you allow a person to continue working when you know that they won't make it, you steal a portion of their life, time they could spend finding a place where they can flourish.

If you're honest with yourself, the reason you wait too long often has less to do with concern for the person and more to do with convenience.

When you know you need to make a people change, act. But be sure you don't have someone in the wrong seat.

Instead of firing people who aren't performing, try to move them once, twice, or even three times to positions where you think they might blossom.

How do you know when you have the wrong person? Two questions can help. First, would you hire them again? Second, if the person told you they were leaving for a new opportunity, are you disappointed or relieved?

3. Put your best people on your biggest opportunities, not your biggest problems

Put your best people on your best opportunities, not your biggest problems. Managing problems can only make you good, building your opportunities is the only way to become great.

If you sell off your problems, don't sell off your best people.

If you create a place where the best people always have a seat, they're more likely to support changes in direction. Always keep your best people, even if they have little or no experience with the new direction.

The only way this happens is if you have a Level 5 atmosphere at the top executive level. Not every executive on the team will become a fully evolved Level 5 leader, but each member must transform their personal ambition into ambition for the company.

It's somewhat paradoxical, but you need executives who can, as Jeff Bezos says, disagree and commit.

First who, great companies, and a great life

Adherence to the idea of first who might be the closest link between a great company and a great life. When you have the right people around you and put the right people in the right seats, you don't have to be at work at all hours of the day and night.

And when you are at work, it'll be with people you like.

Members of the good-to-great teams tended to become and remain friends for life. In many cases, they're still in close contact with each other years, or even decades, after working together.

They enjoyed each other's company and many characterized their years on the good-to-great teams as the high points of their lives.

No matter what you achieve, if you don't spend the majority of your time with people you love and respect, you can't possibly have a great life. If you spend the vast majority of your time with the right people, then you'll almost certainly have a great life, no matter where the bus goes.

Confront The Brutal Facts (Yet Never Lose Faith)

The good-to-great companies faced as much adversity as the comparisons. It was how they responded that was different.

They confronted the facts head-on, focused on the few things that would have the greatest impact, and emerged from adversity stronger.

When you start with an honest effort to find the truth, the right decisions often become self-evident. Not always, but often.

Even if all decisions don’t become self-evident, one thing is certain: It’s impossible to make good decisions without confronting the facts.

This is why every company that went from good to great created a culture where people, and ultimately, the truth could be heard.

They operated on both sides of the Stockdale Paradox: retaining absolute faith that they could and would prevail in the end, regardless of difficulties, while confronting the facts of their reality.

Facts are better than dreams

Good-to-great companies didn’t have a perfect record, but on the whole they made more good decisions than bad ones, and on the really big choices, they were remarkably right.

This begs the question:

“Were Jim and his team merely studying a set of companies that stumbled upon the right decisions? Or was there something distinctive about their process that increased the likelihood of being right?”

It turns out there was. The good-to-great companies confronted the facts of their reality, and the comparison companies generally did not.

This leads to the next finding. Strong, charismatic leaders can all too easily become the de facto reality driving a company. The comparison companies often had leaders who led with such force that people worried more about what they thought than reality and what it could do to the company.

This is why less charismatic leaders often produce better long-term results. If you have a strong, charismatic personality, understand that charisma can be as much of a liability as an asset.

Your strength of personality can cause people to hide the facts from you.

You can overcome this, but it does require conscious effort.

A climate where the truth is heard

You might be wondering, “How do you motivate people to confront the facts? Doesn’t motivation flow from a compelling vision?”

The answer is surprisingly no.

Not because vision is unimportant, but because expending energy trying to motivate people is a waste of time.

If you have the right people, they will be self-motivated. The key is to not de-motivate them.

And one of the primary ways to do this is by ignoring reality.

Yes, leadership involves vision. But it’s equally about creating an environment where the truth can be heard and acted on.

This involves four practices:

Leading with questions, not answers

Engaging in dialogue, not coercion

Conducting autopsies, without blame

Building red flag mechanisms

1. Leading with questions, not answers

Resist the urge to provide the answer. Instead, operate in a Socratic style and use questions to gain understanding.

Keep asking questions until you have a clear picture of reality and its implications.

Never use questions as a form of manipulation or a way to blame or put down others.

Spend the bulk of your time just trying to understand.

Start with questions like:

What’s on your mind?

Can you tell me about that?

Can you help me understand?

What should we be worried about?

Open-ended questions tend to bubble current realities to the surface.

2. Engaging with dialogue, not coercion

The good-to-great leaders often played the role of a Socratic moderator in a series of raging debates. People would scream, argue, and fight, then emerge with a conclusion.

In the words of Jeff Bezos, they would disagree and commit.

Nearly all the good-to-great executives described climates where the company’s strategy evolved through arguments and fights. Phrases like “loud debate,” “heated discussions,” and “healthy conflict” were common.

Discussions weren’t a sham process to let people have their say so they would buy in to a predetermined decision. Discussions were how they found the right answers.

3. Conducting autopsies, without blame

Good-to-great companies spent hundreds, if not thousands, of people hours analyzing mistakes, but no one pointed fingers.

Unless it was the CEO standing in front of the mirror blaming themselves.

This is contrarian in an era where leaders go to great lengths to preserve their image and step forth to claim credit for how visionary they are while blaming others when their decisions go awry.

By conducting autopsies without blame, you create a climate where the truth can be heard. And if you have the right people, you shouldn’t need to assign blame.

Focus on understanding and learning from mistakes.

4. Building red flag mechanisms

More information is supposed to be an advantage. But if you look across the rise and fall of organizations, you rarely find companies stumbling because they lack information.

There was no evidence that the good-to-great companies had more, or better, information than the comparisons. Both sets had virtually identical access to information.

The key is not better information, but making sure that information cannot be ignored. One particularly powerful way to accomplish this is through red flag mechanisms. One example is to tell customers to not pay you if they aren’t satisfied for any reason without the need to return the product.

This works because it creates hard-to-ignore feedback.

The Stockdale paradox

The good-to-great companies faced just as much adversity as the comparison companies, but how they responded was different.

On the one hand, they stoically accept reality. On the other, they maintained an unwavering faith in the endgame, and a commitment to prevail as a great company despite reality.

Jim and his team came to call this duality the Stockdale Paradox named after Admiral Jim Stockdale, the highest-ranking US military officer in the “Hanoi Hilton” prisoner-of-war camp between 1965 and 1973.

Stockdale lived out the war without any rights, no set release date, and no certainty as to whether he would even survive to see his family again.

When Jim asked Stockdale how he dealt with it, he said “I never doubted not only that I would get out, but also that I would prevail in the end and turn the experience into the defining event of my life, which, in retrospect, I would not trade.”

This sounds optimistic, but when Stockdale was asked who didn’t make it out, he said:

“Oh, that’s easy, the optimists. They were the ones who said, ‘We’re going to be out by Christmas.’ And Christmas would come, and Christmas would go. Then they’d say, ‘We’re going to be out by Easter.’ And Easter would come, and Easter would go. And then Thanksgiving, and then it would be Christmas again. And they died of a broken heart.”

What separates people, and companies, is not the presence or absence of difficulty, but how they deal with it.

If you adopt this dual pattern, you dramatically increase the odds of making a series of good decisions, and ultimately discovering a simple, yet insightful, concept for making the really big choices.

The Hedgehog Concept (Simplicity within the Three Circles)

Isaiah Berlin divided the world into hedgehogs and foxes, based on the ancient Greek parable: “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”

Hedgehogs simplify the world into a single organizing idea, basic principal, or concept that unifies or guides everything.

On the other hand, foxes pursue many things at the same time and see the world in all its complexity.

To be clear, hedgehogs aren’t stupid. Quite the opposite. They understand the essence of insight is simplicity. They take a simple idea and take it seriously, and this is what allows them to see through complexity and discern underlying patterns.

Hedgehogs see what’s essential and ignore the rest.

Those who build good-to-great companies are more like hedgehogs. They know one big thing and stick to it. The comparison companies tended to be foxes, crafty, cunning, and knowledgeable, but never gaining the clarifying advantage of a Hedgehog Concept.

The three circles

To go from good to great requires a deep understanding of your Hedgehog Concept, then using that concept to guide all your efforts.

This comes at the intersection of three circles:

What you can (and can not) be the best at: This goes beyond core competence. Competence doesn’t necessarily mean you can be the best in the world at it. Inversely, what you can be the best at might not even be something you’re currently doing.

What drives your economic engine: You need insight into how to generate sustained and robust cash flow and profitability. In particular, a single denominator–profit per x–that has the greatest impact on your economics.

What you are deeply passionate about: Focus on activities that ignite your passion.

Understanding what you can (and can not) be the best at

The most important thing to understand is what you can be the best at, and equally, what you cannot be the best at. Not what you want to be the best at.

This distinction is crucial.

Your Hedgehog Concept isn’t a goal, strategy, or intention. It’s an understanding.

If you cannot be the best in the world at your core business, then your core business cannot be the basis of your Hedgehog Concept.

Best in the world is a much more severe standard of excellence than a core competence. You might be competent, but not necessarily have the capacity to truly be the best in the world.

Inversely, there may be activities you could be the best in the world at but have no current competence.

Understand what you can truly be the best at, then stick to it.

Doing what you are good at will only make you good. Focus solely on what you can do better than anyone else.

Insight into your economic engine – what is your denominator?

You don’t need to be in a great industry to build a fantastic economic engine. The good-to-great companies often produced specular returns in unspectacular industries.

You need a deep understanding of the key drivers of your economic engine and you need to build a system in accordance with this understanding.

You need a single economic denominator.

To find it, ask yourself:

“If I could pick one and only one ratio–profit per x–to systematically increase over time, what x would have the greatest and most sustainable impact on my economic engine?”

This question leads to profound insight into the inner workings of your economics.

Push for a single denominator. It’ll produce better insight than letting yourself off the hook with three or four.

Understanding your passion

It may seem odd to talk about something as fuzzy as passion as an integral part of your strategy. But passion is a key part of the Hedgehog Concept.

It’s not about saying, “Let’s get passionate about what we do.” Rather, you should only do things that you are or can get passionate about.

This doesn’t mean that you have to be passionate about the mechanics of the business. The passion circle can equally focus on what the company stands for.

Remember, you can’t manufacture passion or “motivate” people to feel passionate. You can only discover what ignites your passion and the passions of those around you.

The triumph of understanding over bravado

Set your goals and strategies based on the intersection of the three circles, not bravado.

Setting goals based on bravado is most obvious in the mindless pursuit of growth.

“Growth” is not a Hedgehog Concept.

However, if you have the right Hedgehog Concept and make decisions consistent with it, you create momentum and your main problem becomes not how to grow, but how to not grow too fast.

Finding your Hedgehog Concept is a turning point for going from good to great.

But it’s a terrible mistake to thoughtlessly try to jump right to a Hedgehog Concept. Discovering your Hedgehog Concept is an inherently iterative process, not an event.

On average, it takes about four years to clarify.

The council

A useful device for iterating toward your Hedgehog Concept is the Council.

The Council is a group of five to twelve people who ask questions guided by the three circles:

Do we know what we can be the best in the world at?

Do we understand the drivers of our economic engine, including our economic denominator?

Do we understand what best ignites our passion?

Every member must be able to argue and debate the answers, while maintaining the respect of every other Council member, without exception.

The goal isn’t to seek consensus. The responsibility for the final decision remains with the leading executive.

But once the decision is made, the Council should perform an autopsy and analysis of the results and repeat the process periodically, as much as once a week, or as little as once a quarter.

Members should come from a range of perspectives, but each must have deep knowledge about some aspect of the organization or environment.

This typically includes key members of management, but is ’t limited to management, and being an executive does ’t automatically make you a member.

Your hedgehog concept

Most companies aren’t the best in the world at anything, and show no prospect of becoming so. But every company has a Hedgehog Concept to discover.

There’s something you can become the best at, and you can find it. But only if you confront the facts of what you cannot be the best at, no matter how awful your starting point.

As you search for your own, keep in mind that when you finally grasp your Hedgehog Concept, it’ll be free of bravado and feel more like a recognition of a fact.

Once you successfully apply these ideas, don’t stop. The only way to remain great is to keep applying the fundamental principles that made you great.

Culture of discipline

Few startups become great companies because as scale introduces complexity, it becomes easier and easier to trip over your own success.

Too many people. Too many customers. Too many products. Too many problems.

In response, someone (usually from the board) says, “It’s time to grow up.” In come the MBAs and seasoned executives. And with them come processes, procedures, and checklists.

The self-organizing, egalitarian environment is replaced with strict hierarchy, chains of command, and complex reporting structures. These professionals managers do rein in the mess, but they all too often kill the thing that got them there in the first place – entrepreneurial spirit. And members of the founding team start to grumble:

“This isn’t fun anymore.” “I can’t get anything done.” “I’m always stuck in stupid meetings.”

Once your most innovative people leave, your once exciting startup transforms into any old company, and mediocrity creeps in. The issue is companies build bureaucracy to compensate for incompetence and lack of discipline – two things that largely don’t exist when you have the right people.

And if you lean too heavily on managing the small percentage of people who shouldn’t be on the bus, you’ll drive away the right people, which increases the percentage of the wrong people and the need for hierarchy, and so on.

The best companies avoid bureaucracy and instead create a culture of discipline that enables creativity and entrepreneurship, instead of stifling it.

More precisely, they:

Give people freedom and responsibility, within a framework.

Hire self-disciplined people who go to extreme lengths to fulfill their responsibilities.

Don’t confuse a culture of discipline with a tyrannical disciplinarian.

Adhere to the Hedgehog Concept and focus on the intersection of the three circles.

Create a “stop doing list” and unplug from the extraneous.

When you combine a culture of discipline with an ethic of entrepreneurship, you get superior performance and sustained results.

Freedom (and responsibility) with in a framework

Much of the answer to what it takes to go from good to great lies in the discipline to do whatever it takes to become the best in the world in a carefully selected arena, and then to seek continual improvement from there.

It’s simple, but not easy.

Everyone wants to be the best, but most people lack the discipline to figure out with egoless clarity what they can be the best at and the will to turn that potential into reality.

The good-to-great companies built consistent systems with clear constraints, but also provided people with freedom and responsibility within those systems. The only way this works if you have people who believe in the system and will do whatever it takes to make it work.

But how do you get to a place of such conviction?

It starts with disciplined people, but don’t conflate this with disciplining people into the right behavior. You need the right people on the bus.

Then you need those people to engage in disciplined thought. They need to confront the brutal facts and persist until you find your Hedgehog Concept.

Only once you’ve found your Hedgehog Concept can you focus on disciplined action.

The order here is essential. You can’t jump to the end.

Disciplined action without disciplined people is impossible to sustain, and discipline alone doesn’t guarantee results. There are plenty of companies with tremendous discipline who march right into disaster.

Disciplined people must engage in disciplined thought, and only take action within a consistent system designed around their Hedgehog Concept.

A culture, not a tyrant

Every unsustained comparison followed the same pattern: a spectacular rise under a tyrannical disciplinarian, followed by an equally spectacular fall when the disciplinarian stepped away.

The leaders of the unsustained comparisons personally disciplined their organization through sheer force of personality, acting as the company’s primary quality control mechanism.

In contrast, the Level 5 leaders at the good-to-great companies built enduring cultures of discipline that outlasted them.

Fanatical adherence to the Hedgehog Concept

The good-to-great companies at their best followed one rule: “Anything that does not fit with our Hedgehog Concept, we will not do.” They did not launch unrelated businesses, they did not make unrelated acquisitions, nor did they go after unrelated “once-in-a-lifetime opportunities”.

If it didn’t fit, they didn’t do it.

This is because great companies are more likely to die of indigestion than starvation. The challenge is opportunity selection, not creation.

In contrast, the lack of discipline to stay within the three circles was a key factor in the demise of nearly all the comparison companies. Every comparison either lacked the discipline to understand its three circles or to stay within them.

Few companies have the discipline to discover their Hedgehog Concept, and fewer still have the discipline to build consistently within it.

Start a “stop doing” list

Most of us lead busy lives with expanding to-do lists, trying to build momentum by doing more, but it rarely works. Those who built the good-to-great companies made as much, if not more, use of stop doing lists.

They had a remarkable knack for removing the extraneous and they institutionalized the practice through budgeting. Most people think the purpose of budgeting is to decide how much to apportion to each activity or to manage costs.

This is wrong. The budget process is not for figuring out how much each activity gets, rather it’s about determining which activities best support the Hedgehog Concept and which should be eliminated entirely.

Budgeting should be used to decide which areas should be fully funded, and which should not be funded at all. The good-to-great CEOs didn’t reallocate resources, they eliminated everything that didn’t align with their Hedgehog Concept.

It takes remarkable courage to channel all your resources into a few areas, but they rarely hedged their bets. After all, the most effective investment strategy is a highly concentrated strategy, if you are right.

This sounds facetious, but it’s the approach the good-to-great companies took. Once they found their Hedgehog Concept, they invested fully in things that fit squarely in their three circles, and got rid of everything else.

Technology accelerators

In every good-to-great transition, there was technological sophistication. However, their transitions never began with the adoption of new technology. At the same time, they all became pioneers in the application of the technologies that they adopted.

The most important thing to understand is technology is only ever an accelerant, not a creator, of momentum. You could give the exact same technology to the comparison companies and they would have failed to produce the same results as the good-to-great companies.

Technology and the hedgehog concept

You can’t make good use of technology without knowing which technologies are relevant to you. The question you need to answer when adopting any technology is: “Does this technology fit with my Hedgehog Concept?”

If it does, you need to become a pioneer in the application of that technology. If it doesn’t, you need to ask yourself whether you need it at all. If you do, then aim for parity. If you don’t, ignore it completely.

Deciding on which technology to adopt is another example of good-to-great companies remaining disciplined. Their relationship to technology is no different than their relationship to any other decision: Disciplined people engage in disciplined thought, and take disciplined action.

If something new doesn’t fit within your three circles, ignore the hype. If it does, become fanatical about its adoption. Technology without a clear Hedgehog Concept, and without the discipline to stay within the three circles, cannot make a company great.

The technology trap

The idea that technology is the principal cause of decline of companies is not supported by research. Companies cannot remain laggards and hope to be great, but technology alone isn’t the primary cause of greatness or decline.

In fact, 80 percent of the good-to-great executives who were interviewed didn’t mention technology as one of the top five factors in their transition. And in the cases where they did mention it, it had a median ranking of fourth. Only two executives of eighty-four interviewed ranked technology as their primary factor.

If technology is so important, why was it so deemphasized? Not because they ignored technology. They all leveraged technology and many received extensive media coverage about their pioneering use of it.

It’s because mediocre results stem from management failure, not technological failure. Remember, the adoption, or lack thereof, technology is an accelerator, not a cause. A failure to adopt technology is simply that principle operating in reverse.

Technology and the fear of being left behind

Those who built the good-to-great companies weren’t motivated by FOMO or their competitors. They were motivated by creative urge and an inner compulsion for excellence for its own sake.

“No technology, no matter how amazing—not computers, not telecommunications, not robotics, not the Internet—can by itself ignite a shift from good to great. No technology can make you Level 5. No technology can turn the wrong people into the right people. No technology can instill the discipline to confront brutal facts of reality, nor can it instill unwavering faith. No technology can supplant the need for deep understanding of the three circles and the translation of that understanding into a simple Hedgehog Concept. No technology can create a culture of discipline. No technology can instill the simple inner belief that leaving unrealized potential on the table—letting something remain good when it can become great—is a secular sin.”

The flywheel and the doom loop

Picture a heavy flywheel—a metal disk mounted horizontally on an axle, 30 feet in diameter, 2 feet thick, and weighing about 5,000 pounds. Your task is to get the flywheel spinning as fast and long as possible.

Pushing hard, you get the flywheel to inch forward, almost imperceptibly. You keep pushing and pushing, after hours of effort, you get one complete turn. You keep pushing, and the flywheel moves faster and with continued effort, you get a second rotation. Three turns, four, five, six, the flywheel speeds up, seven, eight, nine, ten.

Momentum is building. Eleven, twelve, each turn moving faster than the last.

Then, at some point—breakthrough! Momentum turns in your favor, hurling the flywheel forward, turn after turn. Its own weight now works for you. You’re pushing no harder than the first rotation, but the flywheel goes faster and faster.

Each turn of the flywheel builds upon work done earlier, compounding your effort.

Now suppose someone asks you, “What was the one thing that caused your flywheel to spin so fast?”

You can’t answer. It’s a nonsensical question. It wasn’t the first, second, or fifth push. It was all of them added together in an accumulation of effort in a consistent direction. No single effort, no matter how large, outweighs the cumulative effect.

Build up and breakthrough

The flywheel captures what it feels like to be inside a company going from good to great. No matter how dramatic the end result, good-to-great transitions never happen in one fell swoop. There is no single action, no grand program, no killer innovation, no lucky break, no revolution.

Good to great is a cumulative process—step by step, action by action, choice by choice, turn by turn of the flywheel—that adds up to sustained and spectacular results.

But if you read media accounts of each company, you may draw a different conclusion. Often, the media doesn’t cover a company until its flywheel is already spinning. This skews our perception of how transformation occurs, making it seems like they jumped from nothing to breakthrough overnight.

It’s often as if the company hadn’t even existed prior to its discovery, despite the remarkable process made by the team in the decade leading up to the breakthrough point. You may be thinking, “Of course we should expect that. Companies get more coverage as they become more successful. What’s so insightful about that?”

Don’t allow the way transitions look from the outside to drive your perception of what they feel like for those on the inside. From the outside, they look dramatic. From the inside, they feel like a cumulative process.

The good-to-great executives couldn’t pinpoint a single key event that exemplified the transition. Frequently, they chafed against the idea of allocating points and prioritizing factors. It was a whole bunch of interlocking pieces built upon themselves.

The transition wasn’t like night and day. It was gradual and wasn’t entirely clear until years into it. The good-to-great companies didn’t even name their transformations. There was no launch event, no tag line, no programmatic feel whatsoever.

Some executives said that they weren’t even aware that a major transformation was under way until they were well into it. It was more obvious to them after the fact. There was no miracle moment. It was a quiet, deliberate process of figuring out what needed to be done to create the best results and then taking those steps, one after the other.

After pushing on their flywheel in a consistent direction over an extended period of time, they hit a point of breakthrough. Lasting transformations from good ot great follow a general pattern of buildup followed by breakthrough.

Not just a luxury of circumstance

Understand that following the buildup-breakthrough flywheel model isn’t a luxury of circumstance. People like to say,. “we’ve got constraints that prevent us from taking this longer-term approach.”

The good-to-great companies followed this model no matter how dire their short-term circumstances. This also applies to managing the short-term pressure of investors. You communicate with investors, educate them on what you are doing and where you are going. If people don’t buy into that in the short term—you have to wait and let the results of your work do the heavy lifting.

All the good-to-great companies effectively managed investors during their buildup-breakthrough years, and saw no contradiction between the two. They simply focused on accumulating results, under-promising and overdelivering. And as their flywheel built momentum—the investing community came along.

The flywheel effect

There is power in continued improvement and delivery of results. Point to tangible accomplishments—however small—and show how these steps fit into the context of an overall concept that will work.

When people see and feel the buildup of momentum, they line up with enthusiasm. This is known as the flywheel effect, and it applies not only to investors but also to employees.

What’s interesting is that none of the good-to-great leaders found that creating alignment was difficult. Clearly, all the good-to-great companies had incredible alignment, they just never spent much time thinking about it. Under the right conditions, issues with commitment, alignment, motivation, and change take care of themselves.

The good-to-great companies tended not to publicly proclaim big goals at the outset. Instead focusing their efforts on turning the flywheel, creating tangible evidence that their plans made sense. Once the flywheel was spinning, people wanted to keep it going.

When you let the flywheel do the talking, you don’t need to constantly communicate your goals. When people feel the magic of momentum and begin to see tangible results, the bulk of people line up to start pushing the flywheel harder.

The doom loop

There was a very different pattern at the comparison companies. Instead of a quiet, deliberate process of figuring out what needed to be done and simply doing it. The comparison companies frequently launched new programs, only to see the programs fail to produce sustained results.

They would push the flywheel in one direction, stop, change course, and throw it in a new direction, and then they would stop and change course again. After years of lurching back and forth, the comparison companies failed to build momentum and fell into the doom loop.

While the specific permutations of the doom loop varied from company to company, there were two prevalent patterns:

The misguided use of acquisitions: The drive for M&A often comes from the fact that doing deals is more exciting than doing actual work. Good-to-great companies used acquisitions after the development of their Hedgehog Concept and after the their flywheel had significant momentum. Acquisitions were accelerants, not creators of momentum. In contract, the comparison companies consistently reached for an acquisition or merger to increase growth, diversify away from troubles, or make a CEO look good.

The selection of leaders who undid the work of previous generations: The other common doom loop pattern is that of new leaders who stepped in, stopped a spinning flywheel, and threw it in a new direction.

The flywheel as a wraparound idea

Consistency and coherence came up over and over in the good-to-great transformations. Coherence is an idea from physics, the magnifying effect of one factor upon another. Each piece of the system reinforces another piece of the system to form an whole that is more powerful than the sum of its parts. Consistency over time, through multiple generations, gets maximum results.

It starts with Level 5 leaders. They’re less interested in flashy programs that make it look like they’re leading, and more interested in the quiet deliberate process of pushing the flywheel.

Getting the right people on the bus, the wrong people off the bus, and the right people in the right seats are all crucial steps in the early stages of buildup. Equally important is to remember the Stockdale Paradox. You might not hit breakthrough this year, but if you keep pushing, you will eventually.

This process of confronting the brutal facts helps you see the obvious, albeit difficult, steps that must be taken to turn the flywheel. Next, you must attain deep understanding of the three circles of your Hedgehog Concept and begin to push in a consistent direction, accelerating by pioneering the application of technology tied back to your three circles.

Breakthrough comes from having the discipline to make a series of good decisions consistent with your Hedgehog Concept—disciplined action, following from discipline people who exercise disciplined thought. That’s it.

Once you get there, the challenge is no longer about how to go from good to great, but how to stay consistently great.

From good to great to built to last

Built to Last, one of Jim’s books published prior to Good to Great, is based on a six-year research project conducted at Stanford Business School to answer the question, “What does it take to start and build an enduring great company from the ground up?”

Much like Good to Great, Jim and his coauthor Jerry I. Porras studied 18 enduring great companies and 18 paired comparisons. In short, they short to identify the differences between good and great companies as they endured over decades and centuries.

Early in the research, they made the decision to conduct the Good to Great research as if Built to Last didn’t exist to ensure they could identify the key factors in transforming from a good company to a great one with minimal bias from prior work.

With both studies complete, Jim had four conclusions:

The early leaders of the enduring great companies in Built to Last followed the good-to-great framework. The only difference was that they did so as entrepreneurs in early-stage companies rather than CEOs trying to transform established companies.

Good to Great is really a prequel to Built to Last. Applying its findings creates sustained great results, then applying the findings in Built to Last can help you go from great results to enduring great company.

Shifting from a company with sustained great results to an enduring company means discovering core values and purpose beyond making money and combining this with the dynamic preserve the core/stimulate the process.

There is tremendous resonance between the two studies: the ideas in each enrich and inform the other. In particular, Good to Great answers the fundamental question raised in Built to Last: “What is the difference between a good and a bad big hairy audacious goal (BHAG)?”

Core ideology: The extra dimension of enduring greatness

The “extra dimension” that helped elevate great companies to enduring great companies is a core ideology, which consists of core values and core purpose beyond making money.

Enduring great companies don’t exist merely to deliver returns to shareholders. Profits and cash flow are like blood and water to a healthy body: Absolutely essential, but not the point of life.

An important caveat is that there are no “right” core values for becoming an enduring great company. Core values are essential to enduring greatness, but it doesn’t seem to matter what the core values are. Enduring great companies preserve their core values and purpose while their business strategies and operating principles adapt. This is the magical combination of preserve the core and simulate progress.

Good BHAGs, bad BHAGs, and other conceptual links

Good to Great provides the core ideas for getting a flywheel turning from buildup through breakthrough, while Built to Last outlines the core ideas for keeping a flywheel accelerating over the long term. The four key ideas from Built to Last are:

Clock Building, Not Time Telling. Build an organization that can endure and adapt through generations of leaders and product life cycles; the exact opposite of being built around a single great leader or idea.

Genius of AND. Embrace both extremes on a number of dimensions at the same time. Instead of choosing A OR B, figure out how to have A AND B.

Core Ideology. Instill core values (essential and enduring tenets) and core purpose (fundamental reason for being beyond making money) as principles to guide decision making and inspire people.

Preserve the Core/Stimulate Progress: Preserve the core ideology as an anchor point while stimulating change, improvement, and renewal in everything else. Change practices and strategies while holding core values and purpose fixed. Set and achieve BHAGs consistent with the core ideology.

There is a clear connection between BHAGs and the three circles of the Hedgehog Concept. BHAGs are a key way to stimulate progress while preserving the core. A BHAG, Big Hairy Audacious Goal, serves as a unifying focal point of effort.

Good BHAGs are set with understanding. Bad BHAGs are set with bravado.

A good BHAG, while huge and daunting, is not a random goal. It’s a goal that makes sense within the context of the three circles. To remain great over time requires staying squarely within the three circles while being willing to change the specific manifestation of what’s inside the three circles at any given moment.

To create an enduring great company requires all the key concepts from both studies, tied together and applied consistently over time. If you ever stop doing any one of the key ideas, you will inevitably slide toward mediocrity. And remember, it’s easier to become great than remain great.

Why greatness?

First, it is no harder to build something great than to build something good. It might be rarer, but it does not require more suffering than mediocrity. If some of the comparison companies are any indication, it may involve less suffering, and perhaps less work.

The key thing to realize is that much of what you do at work is at best a waste of energy. If you organize the majority of your work time around applying these principles, and ignore or stop doing everything else, your life will be simpler with better results. If it’s no harder, the results better, and the process more fun—why wouldn’t you go for greatness?

There is a second answer to the question of why greatness, meaningful work.

If you’re doing something you care about and believe in its purpose deeply, then it’s impossible to imagine not trying to make something great, and then the question becomes not why, but how.