High Output Management by Andy Grove

A summary and review of Andy Grove's book, High Output Management.

High Output Management by Andy Grove is widely considered to be the best book on management and by the end of this post, you’ll understand why.

I think Tobi Lutke, the co-founder and CEO of Shopify, put it best in an interview with Tim Ferriss:

Andy’s book is unapologetically almost a how-to manual, that kind of deconstructs the world of business into first principles. It’s like, “Here’s what matters. Here’s how to think about it. No one needs a degree.”

I find books easier to remember when I have context about the person who wrote them, so I think it’s fitting to start with Andy Grove himself.

Andy Grove escaped the ruins of postwar Europe and became one of the architects of Silicon Valley and the modern world as we know it.

He was born to a middle-class Hungarian Jewish Family on Sept. 2, 1936 and his early life is summarized in his memoir Swimming Across:

I had lived through a Hungarian Fascist dictatorship, German military occupation, the Nazis' “Final Solution”, the siege of Budapest by the Soviet Red Army, a period of chaotic democracy in the years immediately after the war, a variety of repressive Communist regimes, and a popular uprising that was put down at gunpoint.

Heeding the word of his aunt who had survived Auschwitz, Andy joined the flood of refugees who escaped Hungary via Austria in hopes of a better life in the West.

He arrived in the United States at 21, barely able to speak English with less than $20 to his name.

By 31, Andy had earned his Bachelor's and Ph.D. in chemical engineering, worked at Fairchild Semiconductor for four years, and written a college-level textbook on semiconductors.

Then at 32, Andy made the jump from Fairchild to Intel on the day of its incorporation. Joining its founders Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore as the company's director of engineering and employee number three.

He would go on to establish Intel's early manufacturing operations before becoming President at 43, CEO at 51, and chairman and CEO of Intel at 61.

During his tenure, Intel's revenue grew from $2,672 to $20.8 billion.

High Output Management was born out of Andy's experiences leading Intel. Nearly four decades after its initial publication, High Output Management has reached cult-like status and become a Silicon Valley staple.

CEOs of highly productive teams re-read it, top venture capitalists give copies to startup founders, and every manager worth their salt devours its content.

This is because the book's three core concepts remain true:

You can apply the principles and discipline of manufacturing to management

Work is done by teams not individuals

Teams only perform well when each member is working at their best

If you remember one thing, remember this:

A manager’s output = the output of their organization + the output of the neighboring organizations under their influence

Besides Tobi and Tim, fans of High Output Management include:

Bill Campbell: Former executive coach to Larry Page, Sergey Brin, Eric Schmidt, and Sundar Pichai at Google, Steve Jobs at Apple, Jeff Bezos at Amazon, Jack Dorsey and Dick Costolo at Twitter, and Sheryl Sandberg at Facebook;

Drew Houston: Co-founder and CEO of Dropbox;

Keith Rabois: Partner at Founders Fund, co-founder of Opendoor, former COO at Square, and early employee at LinkedIn and PayPal;

Mark Zuckerberg: Co-founder and CEO of Facebook;

Marc Andreessen: Co-founder of a16z, co-founder of Netscape and Opsware, and co-author of Mosaic;

Ben Horowitz: Co-founder of 16z and co-founder of Opsware;

Brian Chesky: Co-founder and CEO of Airbnb;

Brian Armstrong: Co-founder and CEO of Coinbase; and

Ev Williams: CEO and founder of Medium and co-founder of Twitter.

Learning the basics of production

Before we can apply the principles and discipline of manufacturing to management, we first need to understand the principles of production.

Imagine you're tasked with creating a cafe that sells one dish: a three-minute soft-boiled egg, buttered toast, and coffee.

You must make a profit and each item must be served simultaneously.

While customers would prefer to have meal when they sit down, that would require infinite production capacity or ready-to-serve inventory. Either option eats into your margins, making it harder to sell at a competitive price while making a profit.

What you need a system to deliver breakfasts at a scheduled time, acceptable quality level, and low cost.

In reality, customers don't mind waiting five to ten minutes for breakfast. But how do you ensure that?

Start with the limiting step and plan production around it. The limiting step is the most difficult, sensitive, expensive, or time-consuming step.

When it comes to cooking breakfast, your limiting step is the egg.

It takes the longest, costs the most, and is the crucial part. Using the egg’s cooking time as your base, give yourself enough time to toast the bread.

Use the toasting time to determine when to pour the coffee.

Finally, add the time it takes to plate up and offset each step.

The time it takes to prepare the dish is known as the total throughput time.

Production operations

We can learn three fundamental production operations from cooking breakfast:

Process manufacturing: These are physical or chemical changes to the material like boiling the egg and toasting the bread;

Assembly: When you arrange the egg, toast, and coffee to make a meal; and

Testing: This is when you examine components or the final product for faults like when you check the toast is browned and the coffee is steaming.

Complications

So far we've assumed you won't have to wait for the toaster, can always boil an egg, and will never run out of coffee. In practice, any of these things could happen which would in turn makes them your limiting step. So what can you do?

You can hire specialists: Like a chef or barista but this creates overhead which may be too expensive;

You can invest in capital equipment: Like a new pot, toaster, or coffee maker; or

Create an inventory: You can pre-boil eggs and pre-toast bread but this risks waste.

As the manager, your job is to find the most cost-effective way to deliver the best breakfast in the least time.

You decide to invest in a continuous egg-boiler that provides a constant supply of perfectly boiled three-minute eggs.

Relying on continuous operation means lower flexibility, you can't adjust eggs if requested but customers benefit from lower costs and predictable quality.

Another issue is malfunction. If the egg-boiler malfunctions, the eggs in the machine can’t be sold, and you'll have to throw out the toast because there is nothing to serve with it.

Use a functional test to prevent this. Open up the occasional egg to ensure quality.

Better yet, use in-process inspection and monitor the temperature of the water. Always opt for in-process tests over those that destroy the product.

Eggs could also be cracked, rotten, or take different times to cook, which is why incoming or receiving inspections are important.

If all your eggs are rotten, you'll need to close the cafe for the day. Consider having a raw material inventory capable of covering your consumption rate for the time it takes to replace it.

But inventory costs money, so weigh the pros against cons.

Just don’t forget about the opportunity at risk: how many customers would you lose, and what would it cost to lure them back?

The final thing to remember is that material becomes more valuable as it moves through the production process.

So detect and fix problems at the lowest value possible. Find and reject rotten eggs when they’re delivered, not on when they're on the customer’s plate.

A boiled egg is more valuable than raw, and breakfast in front of the customer is the most valuable.

As it turns out, even managing a cafe with a single dish and no employees is complicated. Just wait until we add more people…

Introduction to Management

Customers like what you're selling. You've made enough to invest in additional staff and automated equipment for the eggs, toast, and coffee.

Your output is no longer the breakfasts you deliver personally. Rather it's the breakfasts your cafe delivers, profits generated, and customer satisfaction.

But how do you track that? You need to come up with indicators focused on specific goals and track progress against them.

Here are the five that I'd pick:

Sales forecast: How many breakfasts should you plan to deliver? To assess how confident you should be in your prediction, you need to measure the variance between breakfasts delivered versus forecasted.

Raw material inventory: Do you have enough eggs, bread, and coffee to get through the day? Have too much? Cancel today’s order. Too little? Order more.

Equipment: Does anything need repair or replacement? If so, rearrange the production flow and/or lower your forecast.

Workforce: Are all staff there? Do you need to move someone from eggs to toast?

Quality: You need to know what customers think. Otherwise, quality may dip as volume increases.

Indicators are essential for guiding your attention and driving decision-making. You need to look at them early each day so you can correct problems before they get out of hand.

At the same time, you need guard against overreacting. Do this by pairing indicators, so effect and counter-effect are measured. For example, increased sales and decreased quality is a problem.

Any measurement is better than none but truly effective indicators focus on output not activity. Indicators that are countable should be paired with indicators that stress quality. Measure breakfasts sold, not the number of eggs boiled.

Indicators:

Outline objectives;

Provide objectivity and measurability; and

Allow comparison of similar teams.

The black box

Think of your cafe as a black box: raw materials and labor go in and breakfast comes out.

Indicators are windows into the black box which allow you to better understand the internal workings of the process without actually doing the work yourself.

Leading indicators show what the future may look like, providing time to take corrective action to avoid problems if needed.

To be effective, you must believe in their validity.

Choose credible indicators, so you act when warning signs appear. Otherwise all you'll get from monitoring is anxiety.

Quality is an excellent leading indicator as a reduction in quality often leads in fewer sales in the future.

Sales are what is known as a trend indicator where output is measured against time (this month vs. last month) and a standard or expected level.

By extrapolating from the past and comparing real results to the forecast, you are forced to think through why. These types of indicators are the best to get a feel for future trends.

You can also use linearity indicators to plot a goal against the month of the year. If everything goes to plan, your numbers should follow a straight line that would hit your target by the end of the period.

If you find yourself below the ideal straight line, you know you can only hit your target if you do better than you've done in the previous months for the remaining time. Linearity indicators give you early warning and time to take corrective action.

As you can tell, indicators are a big help for solving all kinds of issues. If something goes wrong, you have a bank of information ready to analysis. Without them, you're flying blind.

By the time you find a problem and gather the information needed to make a decision, the situation will have gotten worse.

Controlling future output

There are two ways to control output:

Build to order: Making breakfast as requested; and

Build to forecast: Making breakfast in expectation of orders.

Build to order reduces inventory risk but slows production times.

In contrast, build to forecast suffers when orders are higher or lower than the forecast.

When building to forecast, you must run two simultaneous processes:

Manufacturing: Raw material moves through production and becomes a finished good.

Selling: Sales finds prospects and sells the product.

Ideally, these two processes finish at the same time with the order from the prospect arriving just as the product is finished.

In practice, this is rare. Orders might not come in time, customers can change their mind and manufacturing can miss deadlines or hit unforeseen issues.

This is why manufacturing and sales must prepare their own forecasts and work together to determine how much to produce ahead of time.

The more inventory you have, the quicker you can adapt to changes in market conditions.

But inventory costs money. So keep stock at the lowest-value stage possible, which has the highest production flexibility for a given inventory cost: raw eggs, not boiled eggs.

You can apply these same principles to the management of people rather than manufacturing flows. Forecast the number of people you need to accomplish a task and keep slack in the system to account for problems or increased demand.

Assuring quality

Assuring quality in production requires inspection.

The first type of inspection is known as an incoming material inspection or receiving inspection and happens before material enters your black box.

Inspections that occur within your black box are called in-process inspections and inspections that occur before the customer receives the product are called the final or outgoing quality inspection.

Assure quality and reduce costs by rejecting defective material at its lowest-value stage.

When material is rejected at incoming inspection, you have the choice to send it back to the vendor as unacceptable or you can waive your specifications and use it anyway. This latter would likely result in a higher reject rate during in-process and final inspections but may be less expensive than stopping production all together.

The choice you make will generally come down to economics. But never let substandard product reach the customer if it could cause complete failure.

Inspections, like inventory, costs money and interferes with production. So you'll need to balance improving quality while minimizing disturbances.

There are two main techniques to balance these needs:

Gate-like inspection: Holds material until tests are complete then accepts or rejects it. This slows down the manufacturing process.

Monitoring: The bulk of the material flows but you take samples to determine a failure rate.

Monitoring is cheaper and has no comparable slowdown but bad material may escape if this happens you'll need to reject material at a higher-value stage. If the failure rate is too high, you'll need to stop production.

As a rule of thumb, prefer monitoring when experience shows you aren't likely to encounter issues.

Another way to reduce costs is to use variable inspection.

No problem for weeks? Check less often. If problems develop, test frequently until quality returns. Variable review means lower costs and interference.

Productivity

Productivity is output divided by the labor required.

To increase productivity, you can increase the speed you work at or you can change what you do. The latter is the better choice. You want to increase the ratio of output to activity rather than increasing activity itself.

You want leverage. Leverage is output generated by specific work. The higher the leverage, the higher the output you generate for the same amount of activity.

Arrange work in your black box so every activity is high leverage. You can do this through automation and work simplification. If you can automate a task or make it simpler, invest the time to do so.

Remember, increased productivity comes from stressing output and increasing leverage. Increased activity can result in the opposite.

Managerial leverage

Let's first understand what a manager's output is. As a manager you must form opinions, make judgments, provide direction, allocate resources, and detect mistakes. But these are not your output, these are activities that can positively or negatively impact your team's output.

As a manager, your output is equal to the output of your organization plus the neighboring organizations under your influence.

This is because work is done by teams. You can do your individual work well but that is not enough. If you have people reporting to you, your output is the output created by your team and associates.

Even if you don't have any direct reports, if you gather and share information you're a manager. More specifically, a know-how manager and your influence on neighboring teams can be huge.

The most important thing to understand is that the individual work you do as a manager is not output. You need to focus on improving the output of your team and the teams you influence.

Output can be positively or negatively impacted through one or more of the five managerial activities:

Information-gathering: Reading reports, customer complaints, or memos and talking to people inside and outside of the organization. This is the basis of all other managerial work and where you should spend the majority of your time;

Information-giving: Conveying knowledge to members of your team and groups you influence. Beyond facts, you must communicate objectives, priorities, and preferences. This is extremely important because subordinates need the context to know how to make decisions themselves;

Decision-making: Occasionally, you'll make a decision. Prefer to participate in decision-making by offering input, forcing better choices to emerge, reviewing decisions made, and providing feedback. Decisions come in two forms: forward-looking decisions (deciding on an activity set) and responses to developing problems, which can be either technical (e.g. quality control) or involve people (e.g. talking somebody out of quitting);

Nudging: You shouldn't always provide instruction, instead nudge people toward a preferred course of action; and

Role modeling: You are a role model for your organization, subordinates, peers, and even supervisors.

Each of these activities can improve output but you need to spend time where leverage is the greatest. For some, this is in large groups. For others, one-on-one in a quieter, more intellectual environment is best.

Increasing managerial output

For every activity you perform, the output of your organization should increase by some degree. The extent to which it increases is determined by leverage.

Leverage is the measure of output generated by a given activity. The higher the leverage, the more output a given activity produces.

But not every activity increases output and doing more can often reduce output.

That's why the key to high output is focusing on increasing leverage, not activity.

In summary, you can increase managerial productivity in three ways:

By doing things faster

By improving the leverage of existing activities; and

By shifting the mix of activities from low to high leverage

High-leverage activities

High-leverage activities:

Affect many people;

Change a person’s activity or behavior for a long time based on a brief interaction; or

Impact a large group’s work by providing a critical piece of information.

It's important to flag that leverage isn't always a good thing. Just as high-leverage activities can dramatically increase output, high-leverage activities done poorly can dramatically reduce it.

A great example of this is managerial meddling. If you constantly assume control of a subordinate's work, they'll show less initiative in solving their own problems and instead refer the work to you.

The art of management is selecting and concentrating on one, two, or three high-leverage activities and ignoring the rest.

Delegating as leverage

Delegation is an essential part of management.

Given a choice, do you delegate activities you are familiar with or those you that aren’t? Before answering, consider that delegation without monitoring is abdication.

When you delegate, you are still responsible for the task’s completion. Monitoring the delegated task is the only practical way of ensuring that. And it's easier to monitor what you know, so given the choice, delegate activities you know best.

But monitoring should not be confused with meddling. Your goal is to check in to ensure the activity is proceeding along as expected, not to do the work yourself.

Like any production flow, monitor at the lowest-value stage. Review rough drafts, not final reports.

A second principle we borrow from production is variable inspection. Employ different sampling rates for different subordinates. How often you check in should be based on the subordinate's task-relevant maturity, not what you believe they can do in general.

As task-relevant maturity goes up, you monitor less often.

Finally, go into details randomly. Checking everything is equivalent to stopping the product line to check for faults. Remember, always opt for in-process tests over those that stop production.

Production principles for time management

A great deal of your time as a manager is focused on allocating resources: manpower, money, and capital. But the single most important resource you can allocate is your own time. Your time is the only truly finite resource you have.

Improving how you handle your time is the single most important thing you can do to increase output.

You can manage your time better by applying production principles:

Identify the limiting step: Determine what is immovable and manipulate more flexible activities around it.

Batch similar tasks: Everything requires a certain amount of mental set-up. Efficient work relies on grouping related activities.

Build to forecast: The majority of your work should be by forecast, and the medium is your calendar. Most people treat calendars as a place for orders to come in. You should use it as a production planning tool. Schedule work that is not time-critical between the limiting steps of your day. And just as a factory manager says no to additional jobs if the factory is at capacity, you should say no to tasks that would overload your system.

Say no earlier: Stop work before things reach a higher-value stage.

Allow slack in your schedule: One interruption shouldn’t kill your entire day.

Carry a raw inventory: In the form of projects that don’t need to be finished now, but would increase your team’s productivity over the long term. This also prevents you from meddling in your subordinates’ work.

Standardize: While continuing to think critically about what you do and the approaches you use.

How many direct reports should you have?

Too few or too many direct reports reduces your leverage. If your work is supervisory, aim for six to eight direct reports—this ensures half a day per week for each subordinate.

As a know-how manager, aim for six to eight subordinates or equivalent internal customers. Anything less than six to eight direct reports will result in on-the-job retirement or managerial meddling.

Interruptions: the plague of managerial work

Do everything you can to prevent starts and stops in your day. Even if there is an emergency, think about creating indicators that would have provided insight into the problem before it became time-sensitive.

Your work relies on working with other managers. You can only move toward regularity as others do. Do your part by scheduling recurring meetings at the same time each week.

Uncontrolled interruptions are inevitable and most frequently come from subordinates and people outside your team whose work you influence.

Force frequent interrupters to make an active decision about whether the issue can wait. Block out your calendar with a note that says, “I am doing individual work. Please don’t interrupt me unless it can’t wait”.

But understand that interrupters have legitimate problems they need solved. That’s why they're asking you.

To reduce interruptions, batch them into an organized, scheduled form such as scheduled meetings, one-on-ones, or office hours. If held regularly, people will batch questions instead of interrupting you whenever they want.

And just as a manufacturer produces standard products, you should pin down the common types of interruptions you get and prepare standard responses.

Finally, use indicators to reduce the time you spend dealing with interruptions. A good set of indicators means you can answer questions quickly and without the need for ad-hoc research.

The key is to impose a pattern on the way you handle interruptions.

Meetings: The medium of managerial work

Meetings often feel like a waste of time. Just something you need to endure before you can get back to your real job. But remember, as a manager your output is equal to the output of your team and the teams you influence. You can increase or decrease output through one or more of the five managerial activities:

Information-gathering

Information-giving

Decision-making

Nudging; and

Role modeling.

Meetings are nothing more than a medium to do managerial work. You can do any these activities inside or outside of meetings. Just choose the most high leverage medium for what you want to accomplish. The one that produces the most output for the least amount of work.

Meetings fall into two categories:

Process-oriented: These meetings take place on a regular cadence and are designed to promote knowledge sharing and information exchange; and

Mission-oriented: These are ad-hoc meetings designed to solve a specific problem by making a decision.

Process-oriented meetings

To maximize efficiency, infuse process-oriented meetings with regularity. Attendees should know how the session will run, what matters will be discussed, and what the goal is.

By doing this, you ensure that the meeting has minimal impact on output. Process-oriented meetings come in three types:

One-on-ones: Meetings with you and a direct report;

Staff meetings: Meetings with you and all your direct reports;

Operation reviews: Meetings that allow people who don’t frequently meet to meet. Operation reviews should include formal presentations where managers describe their work to other managers who aren’t immediate supervisors, and to peers in other parts of the company.

One-on-ones

One-on-ones are meetings between you and a direct report and are the primary way of maintaining and deepening your relationship. They can be incredible high-leverage because the hour you spend together can impact the report's work for weeks.

The primary purpose of a one-on-one is mutual teaching and information exchange.

You teach your team members your skills, know-how, and suggest ways to approach things while they provide information about what they’re doing and their concerns.

Schedule one-on-ones based on the job- or task-relevant maturity of each report. Have frequent one-on-ones (once a week) with those inexperienced in the specific situation, and less frequently like once a month for experienced veterans.

Carve out at least an hour. Anything less tends to confine people to simple problems that can be solved quickly.

A key thing to understand is that one-on-ones are the report's meeting. They should set the tone and agenda. This increases your leverage because you don't have to create a plan for each of your direct reports.

It's also important because it forces them to think through what they want to talk about in advance.

The meeting typically starts with indicators managed by the report, such as order rates, production output, or project status. Focus on indicators that signal trouble.

You should also cover anything important that has happened since the last meeting: hiring problems, people problems, organizational issues, and new plans. The criteria of inclusion is whether the issue bothers your subordinate.

Your role is to learn and coach. When they have stopped talking about a topic ask another question about it until you feel like you've gotten to the bottom of the problem.

You should both have a copy of the agenda and take notes against it. Taking notes promotes active listening and ensures that actions required by either party aren’t lost. Consider using a “hold” file where you can both accumulate essential but not urgent issues to discuss in the future.

And where possible encourage heart-to-heart conversations. One-on-ones are the perfect forum for getting at subtle work-related problems.

Schedule one-on-ones on a rolling basis. Setting up the next one as the current one ends makes it easy to account for other commitments and avoid cancellations.

Staff meetings

Staff meetings involve you and your team members and allow peers to interact because of this they're an ideal place for decision-making.

Anything impacting more than two people present is fair game. If something degenerates into a conversation between two people, break it off, and move onto something that affects more people. Suggest the two book a separate meeting to discuss.

Staff meetings should be relatively structured with an agenda prepared ahead of time so everyone has a chance to prepare. You should also include unstructured time so people can bring up anything they want. If required, the things brought up in the unstructured time can become part of the agenda of a future meeting.

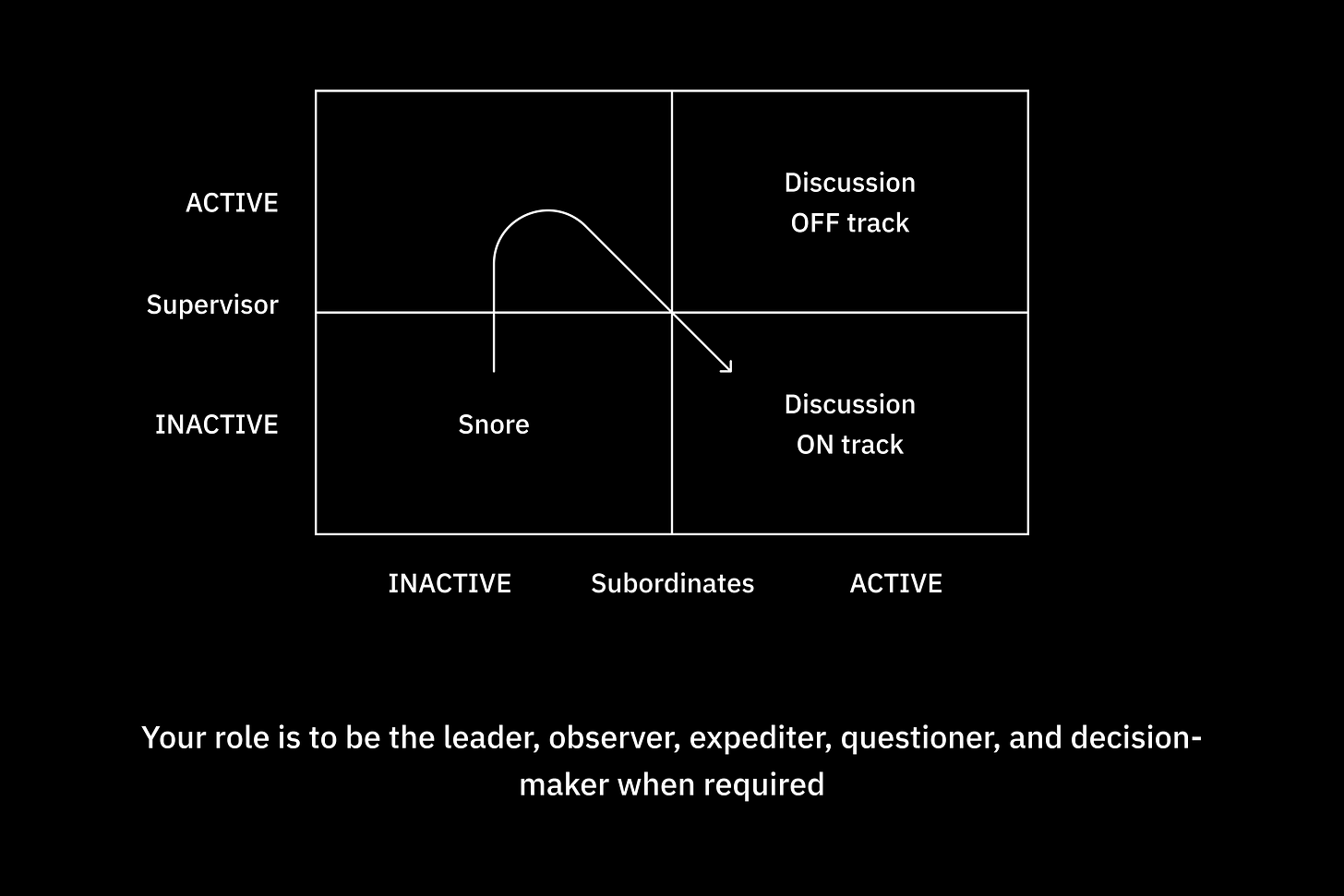

Your role is to be the leader, observer, expediter, questioner, and decision-maker when required.

But ideally, you just keep things on track while your team works out issues.

Operation reviews

Operation reviews are the medium of interaction for those who don’t otherwise have the opportunity to meet. They allow employees several organizational levels apart to teach and learn from each other.

Operation reviews involve four groups:

The organizing manager: They help presenters decide what issues and details to present, book the meeting, and are timekeeper;

The reviewing manager: A senior supervisor whom the review is aimed at. They ask questions, make comments, and are a role model for the junior managers who present;

The presenters: Presenters use visual aids where possible, dedicating four minutes of presentation and discussion to each slide; and

The audience: Audience participation is key so they should questions and make comments.

Mission-oriented meetings

Mission-oriented meetings are ad-hoc and designed to produce a specific output like a decision.

The key to their success is the chairperson, who has the most at stake in the outcome. Usually, this is who calls the meeting.

All too often chairpeople turn up like any other attendee and hope things go as planned. This is why meetings often feel like a waste of time. You need to have a clear understanding of the meeting's objective before you call for it.

So before calling a meeting, ask yourself:

What am I trying to accomplish?

And is a meeting necessary?

If both answers aren’t yes then the meeting will be a waste of time. Likewise, if you are invited to a meeting and the requester can't answer these questions get it cancelled. Meetings are expensive and time is finite.

Assuming a meeting does need to happen, your role is to identify who should attend. If someone can't attend, see if they can send someone in their place.

Remember, mission-oriented meetings are called for a specific purpose. So keep them to no more than six or seven people, decision-making is not a spectator sport.

If you call the meeting you are responsible for the logistics, setting the agenda, and writing the minutes. Once the meeting is over you must share the minutes quickly before attendees forget what happened. They should be clear and as specific as possible, telling the reader what was decided, who is to do it and when.

You need to get attendees the minutes fast before they forget what happened. If writing minutes is too much of a problem, the meeting wasn’t worth calling in the first place.

Ideally, you would never call mission-oriented meetings.

In practice, routine meetings should take care of 80% of problems. Ad-hoc meetings are needed to deal with the rest. If you’re spending more than 25% of your time in ad-hoc meetings, that’s a sign of poor organization.

Decision-making

Making decisions–or more accurately, participating in the decision-making process is an essential part of managerial work. Decision can range from trivial like where to go to lunch to complicated like should we disrupt our own product?

Traditionally, the chain of command was precisely defined and a person's ability to make a decision was dictated by their position in the org chart.

Today, businesses mostly deal with information and know-how. This can cause a large gap between a person's power based on position and another person's power based on knowledge. It's increasingly common that the person who is higher up in the org chart is wrong person to make a decision.

Subordinates often have a better idea of what the right solution is. They're closer to the problem and are immersed in it day-to-day.

The faster the business is changing, the greater the divergence between knowledge and position power will be. Your job as a manager is to ensure that the best decision is made, not that you make the decision yourself.

The ideal decision-making process

The ideal decision-making process begins with free discussion where all points of view and aspects of the issue are openly debated. The greater the disagreement, the more important free discussion is.

When things get heated, people tend to hang back and wait to see what the likely outcome will be. Once they know, they throw their support behind the idea to avoid being associated with the losing position.

All this produces is bad decisions, because knowledgeable people withhold opinions and whatever decision is made is based on information and insight that is less complete than it could have been. A good way to avoid this is to have the most junior person to state their opinion first.

The next step is to reach a clear decision. Again, the greater the disagreement, the more important this step is. You need to articulate the decision and make sure everyone understands. Our natural tendency is to do the opposite.

Once a decision is made, everyone must give their full support.

Not everyone has to agree that it is the right decision, as long as they commit to backing it. As Jeff Bezos says, disagree and commit.

This process may seem simple but it's easier to accept in theory than in practice. It's hard for express your views forcefully, it's hard to make unpleasant decisions, and it's even harder to go against the group. But it's worth doing to reach the best decision.

To recap, the ideal model for decision-making is:

Free discussion: All points of view and aspects of an issue are openly debated regardless of a person's status;

Clear decision: The decision is clearly articulated; and

Full support: Everyone commits to supporting the decision, even if they disagreed prior.

If the decision turns out to be the wrong, go back to step 1.

The final thing you should aim for is to have decisions made at the lowest competent level. Decisions should be made by those who are closest to the situation and know the most about it.

The peer-group syndrome

The most common problem in decision-making is the peer-group syndrome.

People are reluctant share their opinion in the presence of their peers because they fear that their opinion is different to the group's. This leads to a feeling out process where people wait for consensus before taking a position.

If and when a decision emerges it will be stated as the group's opinion, I think our position is...not as a personal opinion. Once this happens the rest of the group buys in and the position becomes solidified.

This is obviously not free discussion and therefore, not the ideal decision-making process.

To prevent this, aim to have peers-plus-one more senior manager in meetings.

Peers tend to look to the more senior manager to take over and shape the meeting. Even if they aren’t the most competent or knowledgeable person involved.

Don't be afraid to sound dumb. Sounding dumb is one of the best ways to surface insights. Remember, every time a fact or insight is withheld the decision-making process is worse off than it could have been.

A related phenomenon that influences lower-level people is the fear of being overruled.

Suppose the group (or senior-level manager) opposes a junior person’s position. If this happens, they may lose face in front of their peers, which is why junior people hang back and let more senior people set the direction.

This is why it's a good idea to have the most junior person in the room speak first.

Six questions to answer before making a decision

While you shouldn't end the free discussion phase too quickly, you can't always reach consensus.

When the time for a decision has arrived, the senior person who has guided, coached, and prodded the group along has to make the decision.

If the ideal-decision making process has been followed, the decision-maker has heard all points of view, facts, opinions, and judgments and has the information needed to make a decision.

Like all other managerial activities, focus on output which in this case is the decision itself.

To avoid blindsiding people, answer these six questions in advance:

What decision needs to be made?

When does it have to be made?

Who will decide?

Who will need to be consulted before making the decision?

Who will ratify or veto the decision?

Who will need to be informed of the decision?

Planning: Today’s actions, tomorrow’s output

Planning is best understood through the lens of our production principles. Recall that a key method of controlling future output is to forecast demand and then build to forecast. If projections don't match reality, you need to increase or decrease production.

These principles apply not only in production but in any planning process. We can break planning into three steps:

Establish environmental demand: What will the environment demand of you, your business, or your organization?

Understand your present status: Where will you be if you change nothing?

Close the gap: Compare and reconcile steps 1 and 2. What more or less do you need to produce to meet projected demand?

Let's dive into each step in more detail.

Step 1: Establish environmental demand

Your environment is defined by the groups that directly influence what you do. This includes your team and any neighboring teams you rely on, your customers, the vendors you use, and the competitors your customers judge you against. You also need to factor in any technological changes that could augment or replace you.

Once you have established your environment, you need to look at it in two time frames: now and in the future.

Ask yourself: what do my customers want now? Am I satisfying them? And what will they expect from me in the future?

The most important thing is to focus on is the difference between your environmental demands now and what you expect them to be.

Don't worry about how you're going to meet demand just yet. Your goal is only to determine whether your current activities are meeting current demands and whether you need to do anything to meet future demand.

Step 2: Understand your present status

Now it's time to determine your present status. List out your current capabilities and projects. As you do this, try to use the same terms you use to state demand. If you define demand in terms of new features or products, your present status should be too.

You also need to factor in that some of the projects you're working on will be scrapped, some of your time will be eaten up by busy work, and that you need slack in your system to account for problems or changes in demand.

Step 3: Close the gap

The final step is to start new tasks or modify existing ones to close the gap between your environmental demand and what your present status will produce.

What do you need to do to close the gap? And what can you do?

Consider each question separately and then decide what you will actually do. It's likely that you won't be able to do everything you want to do. Your strategy should be to choose the actions that produce the most leverage. These are the actions that produce the most output for the least amount of work.

Learn more about strategy by reading my post on 7 Powers.

The output of the planning process

The output of the planning process are the decisions that are made and the actions that are taken. The goal of planning is to produce a set of tasks that are performed now to affect future events.

Ask yourself: what do I have to do today to solve–or better– avoid tomorrow’s problem?

Today’s gap is yesterday’s planning failure.

You should focus and implement only the portion of a plan that lies between now and your next planning process. Everything else you can and will look at again. You should also be careful not to plan too frequently, you need feedback to determine whether the decisions you made were correct.

When planning you need to involve the operating management of the organization. The people planning cannot be separate from the people who are implementing the plan. The leverage you can gain from planning can only be realized by marrying planning and implementation.

Finally, remember that saying yes to one thing is saying no to something else.

Management by objectives and key results (OKRs)

Once demand is well-defined and planning is complete, you can use management by objectives and key results (OKRs). The idea behind OKRs is simple, if you don't know where you're going, you won't get there.

To be successful with OKRs, you need to answer two questions:

Where do I want to go? The answer provides your objective.

How will I know if I am getting there? This gives you your key results.

OKRs are designed to provide feedback relevant to the task at hand and should tell you how you are doing and whether you need to make adjustments. For feedback to be effective, you need to receive it as soon as possible. So OKRs should be set for a relatively short period of time. If you plan for a year, you should set OKRs on a quarterly or even monthly basis.

Keep your number of objectives small. If you focus on everything, you focus on nothing. A few well-chosen OKRs are what make the system work. And if you want to dive deeper into OKRs, I highly recommend Measure What Matters by John Doerr.

Organizational structures

As your organization scales, you'll find that the set of tasks and skills needed to run a small team is very different from those needed to run a large one. The central decision you'll need to make is when to centralize and decentralize decision-making.

If you centralize certain activities, you can do many things at a lower cost and higher quality level. Inversely, centralized decision-making often means you're further from the problem and may not come up with the best solution.

This centralization-decentralization dichotomy is so pervasive that it is one of the most important themes in management.

Recall that management is a team game.

A manager’s output = the output of their organization + the output of the neighboring organizations under their influence

As you scale, management becomes not just a team game but a team of teams game where various teams exist in mutually supportive relationships.

Now let's dive into how organizations can be composed.

Mission-oriented organizations

Mission-oriented organizations are completely decentralized and each business unit pursues its goals with little tie-in to other units. In this model, individual teams are responsible for all elements of their operation from marketing to hiring to developing product.

The only benefit a mission-oriented model provides is that it empowers managers who are closest to the problem to respond to changes in environmental demand fast. All other considerations favor a different model, namely a functional organization.

So why have mission-oriented organizations at all? Because the business of any business is to respond to environmental demand and the need to be responsive is so important that most organizations ends up with mission-oriented groups.

Functional organizations

Functional organizations are at the other extreme and are completely centralized. Decisions are made at headquarters and cascade down with each unit being responsible for a particular discipline across the organization, such as product, growth, engineering, sales, or finance.

The functional model provides obvious economies of scale and allows the expertise of know-how managers in each operational area to be leveraged across the entire organization. It also means you can reallocate resources in response to changes in priorities and business units can focus on mastery.

But there are disadvantages to the functional model. Functional groups suffer from information overload and must respond to demands from different business units that often struggle to adequately communicate their needs. This can lead to internal competition between business units who compete for priority and control of functional groups.

This infighting is clearly a waste of time and resources as it doesn't contribute to the output of the company.

Hybrid organizations

In practice, most companies generally exist between the two extremes of mission-oriented and functional organizations. To quote Grove's Law: All large organizations with a common business purpose end up in a hybrid organizational form.

This mix provides a balance between the responsiveness of mission-oriented units and the leverage provided by functional groups.

The only except to Grove's Law are conglomerates which are typically organized in a totally mission-oriented form. This works when subsidiaries are independent and bear no relationship to one another. But even in this situation, each subsidiary tends to be structured as a hybrid organization.

At the end of the day, each hybrid organization is unique. There are an infinite number of permutations that lie between a totally mission-oriented and a totally functional organization.

In fact, a single organization can and should fluctuation between the two extremes to match the operational styles and aptitudes of its managers.

The most important problem to solve is the optimum and timely allocation of resources and the efficient resolution of conflicts arising over that allocation.

While centralized planning is attractive in theory, it falls over in practice. Centralized planners just can't respond nor predict changes in demand fast enough.

In practice, the answer lies with middle managers who are closest to the problem of generating and consuming internal resources. For middle managers to succeed, two things are necessary:

They must accept the inevitability of the hybrid organization

They must develop and master the practice through which a hybrid organization is managed. Namely, dual reporting.

Dual reporting

Dual reporting, as the name suggests, is when an employee reports to two managers who are jointly responsible for the employee's performance.

The need for dual reporting is fundamental. Think about how a person becomes a manager. The first step in your career was likely as an individual contributor. As you leveled up and improved your skills, you were promoted to more senior positions and then eventually to a management position where you supervised people in your functional speciality.

But at some point, if you keep getting promoted, you'll find yourself as a mission-oriented manager, managing people in disciplines that you have no real experience in. So while you're perfectly capable of managing the more general aspects of the job, you have no choice but to leave the technical aspects to your report.

One solution is to have all employees of a particular discipline report into a functional manager instead of you. But the more you do this, the more you move toward a totally functional organization which as we learned in the last episode reduces your ability to respond to changes in environmental demand.

The desired state is to have the immediacy and operating principles come from the mission-oriented manager while also having technical supervisory come from a functional manager. The solution is dual reporting.

Peer groups as technical supervisors

The role of the technical supervisor doesn't need to be filled by a single person. In fact, it's commonly solved through a peer group who come together to discuss common problems that their mission-oriented bosses can't help them with. In effect, they're now supervised by their boss and a group of peers.

To make this work you need the voluntary surrender of individual decision-making to the group. Being a member means you no longer have complete freedom and must go along with the decisions of your peers most of the time.

This only works if you trust your peers and trust is built on the back of culture. Culture is the set of values and beliefs, as well as the way things are done within a company. A strong and positive culture is essential if dual reporting and decision-making by peers are to work.

This setup makes a manager's life more ambiguous and most people don't like ambiguity. This leads to people looking for something simpler but the reality is that it doesn't exist. Dual reporting in some form is needed to make hybrid organizations work.

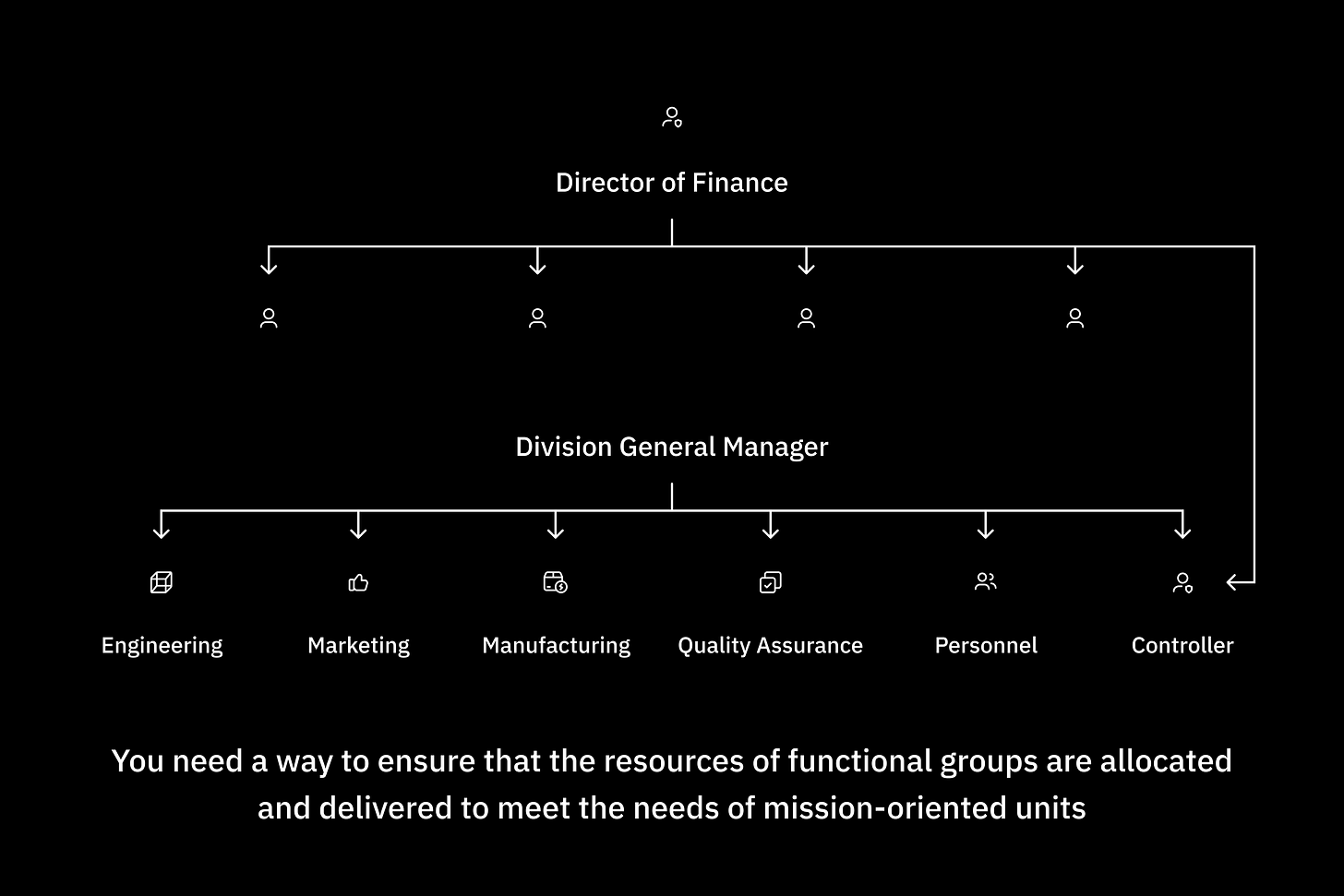

Making hybrid organizations work

To make hybrid organizations work, you need a way to ensure that the resources of functional groups are allocated and delivered to meet the needs of mission-oriented units. The professional methods, practices, and standards are set by the functional manager while general managers give mission-oriented priorities by focusing people on specific problems.

Dual reporting is certainly a tax on productivity as it requires everyone to understand the needs and thought processes of their peers but there is no real alternative when you need to manage hybrid organizations.

Dual reporting and the hybrid organizational form it supports is the inevitable consequence of being a large organization, but should not be an excuse for needless busywork. You still need to remove unnecessary bureaucratic hindrance, apply work simplification, and most of all focus on increasing leverage.

Just don't expect to escape from complexity by playing with reporting arrangements. The hybrid structure is fundamental to any large organization.

The two-plane organization

A subtle variation of dual reporting happens whenever you become involved in coordinating something that is not part of your regular work.

For example, if you work as a sales manager and are part of a committee of sales managers who are responsible for improving the sales processes at your company, you are “reporting” to multiple people.

Your responsibilities can't fit on a single org chart. Instead, the two hierarchies operate on different planes.

This arrangement uses your skills and how-how in two different capacities which allows you to exert much larger leverage on the organization. In your main job, your knowledge improves your team’s performance; in the second, you influence the work of all salespeople at your company.

It also turns out that people who are a subordinate in one plane may be the leader in another. For example, you might be the leader of the sales committee but a subordinate in a strategic planning group.

And if you can operate on two planes, you can likely operate on three or more. The point is that the two- (or multi-) plane organization is very useful. It allows you to be the leader when appropriate and the follower when you are not the most qualified person to lead which gives the organization more flexibility.

The key factors common to all of these arrangements is the use of cultural values as a mode of control.

Modes of control

Our behavior in a work environment is controlled by three invisible and pervasive means:

Free-market forces: Free-market forces apply when actions are based on price like when goods and services are exchanged between two entities seeking to enrich themselves. No one needs to oversee the transaction because everyone is openly serving their own self-interest. Free-market forces fail when value isn't easily defined.

Contractual obligations: When value is hard to define and free-market forces fail, use contracts as the mode of control. A common example of this control are employment contracts which define the kind of work you do and the standards that will govern it. Because it’s hard to specify what people will do day-to-day, you’ll need to have generalized authority to monitor, evaluate, and correct work where necessary; and

Cultural values: When the environment changes faster than rules can or when circumstances are too ambiguous for contracts, use cultural values as the mode of control. The most important characteristic of this control is that the interest of the group must take precedence over individuals. For this to work, you must trust the people you work with and have a common set of values, objectives, and methods which can only be developed through shared experience.

The role of management

Modes of control govern what we do. From one day to the next, you’ll find yourself influenced by all three. When you buy something, market forces are affecting you. When you go to work, you’re adhering to contractual obligations. And when you do work outside your job description to help a colleague, that’s cultural values.

The role of management is to choose the most appropriate mode of control for a given situation.

When free-market forces work, you don't need management. In a contractual obligation, management's goal is to set and modify the rules, monitor adherence, and evaluate and improve performance.

As for cultural values, management needs to develop and nurture a set of common values, objectives, and methods that are essential for the existence of trust. One way to do this is by articulating the values, objectives, and methods. The other, more important way, is by example.

If your behavior at work is in line with the values you profess, you foster the development of culture.

Choosing the most appropriate mode of control

It's tempting to idolize cultural values as the best mode of control. But it's not the most efficient mode of control under all conditions.

What mode of control you use will depend on a person's motivation and the complexity, uncertainty, and ambiguity of their environment. For short, we'll call this the CUA factor.

Let's construct a 2x2 matrix with individual motivation on the Y-axis and the CUA factor on the X-axis. Individual motivation can range from self-interest to group-interest and the CUA factor can range from low to high.

When self-interest is high and the CUA factor is low, free-market forces are the most appropriate mode of control. As individual motivation moves toward group-interest, contractual obligations become most appropriate. If group interest and the CUA factor are high, then cultural values become the best choice. Finally, when self-interest and the CUA factor are high, no mode of control will work well.

Let's apply this model to the work of a new employee. Their motivation is likely based on self-interest so you need to give them a structured job with a low CUA factor. As they do well, they'll start to feel more at home and worry less about themselves and more about their team. They can then be promoted to a more complex, uncertain, and ambiguous job which also tends to pay more.

As time passes and they gain an increasing amount of shared experience with other members of the team, they can tackle more and more complex, ambiguous, and uncertain tasks. This is why promotion from within tends to be preferred by companies with strong cultures.

This is also why it's hard to bring in senior managers from outside the organization. Like any new hire, they come in with high self-interest but likely inherit a job with a high CUA factor. All you can do is hope they quickly move from self-interest to group-interest and just as quickly gets on top of their new role to lower the CUA factor.

The sports analogy

Recall that a manager's output is equal to the output of their team and the teams they influence.

Put another way, management is a team activity. No matter how well a team is structured, no matter how well it is managed, it will only perform as well as the individuals that make it up.

Everything outlined in the previous episodes is useless unless your team continually offers their best. The single most important task of a manager is to elicit peak performance from their team.

You can improve performance by increasing a person's capabilities through training or by increasing motivation.

When a person isn't doing their job, it's because they are incapable or unmotivated.

To determine which, ask yourself: if their life depended on it, could they do it? If yes, they're not motivated. No? they're not capable.

Motivation through Maslow’s hierarchy

For most of history, motivation was based on fear of punishment. If you didn't work hard, you didn't get paid.

This worked because manual labor was readily measurable, departures from the norm were easy to spot, and most people were operating in the lower levels of Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs.

But as the relative importance of manual labor decreases, the corresponding importance of knowledge work increases, and people move into higher levels of Maslow's hierarchy, motivation by fear stops working.

For context, Maslow defined a set of needs that tend to lie in a hierarchy. When a lower need is satisfied, the higher need tends to take over.

Under this model, creating and maintaining motivation relies on some form of dissatisfaction.

Let's take a look at the motivators at each level in more detail.

At the physiological level, one fears the deprivation of food, clothing, and other basic necessities.

At the safety level, the desire to protect yourself from slipping back to the physiological level is the main motivator.

At the social level, you are driven by your inherent desire to belong to a group whose members possess something in common with you.

Our physiological, safety, and social needs are what motivate us to show up to work, but the final two levels of Maslow's hierarchy are what make us perform when we get there.

Our need to keep up with or emulate others is what drives us at the esteem level. It's why we feel the pull to keep up with the Joneses.

But like the other levels, once goals are met, keeping up with people stops being a good motivator.

The final level of Maslow's hierarchy is self-actualization. It stems from the personal realization that "what I can be, I must be". Once motivation is based on self-actualization, the drive to perform is limitless.

Unlike other forms of motivation that extinguish once fulfilled, self-actualization can drive people to ever-higher performance levels.

Some people–not the majority–need to achieve in everything they do and will self-actualize without external input.

For everyone else, management needs to foster an environment that promotes self-actualization by setting objectives high enough that they stretched the outer limits of each person's abilities.

Objectives should be set high enough, so even if individuals push hard, there is only a 50% chance of reaching them.

Output increases when everybody strives for a level of performance beyond their immediate grasp, even if they fail half the time.

The most important thing to do is to create an environment that values and emphasizes output.

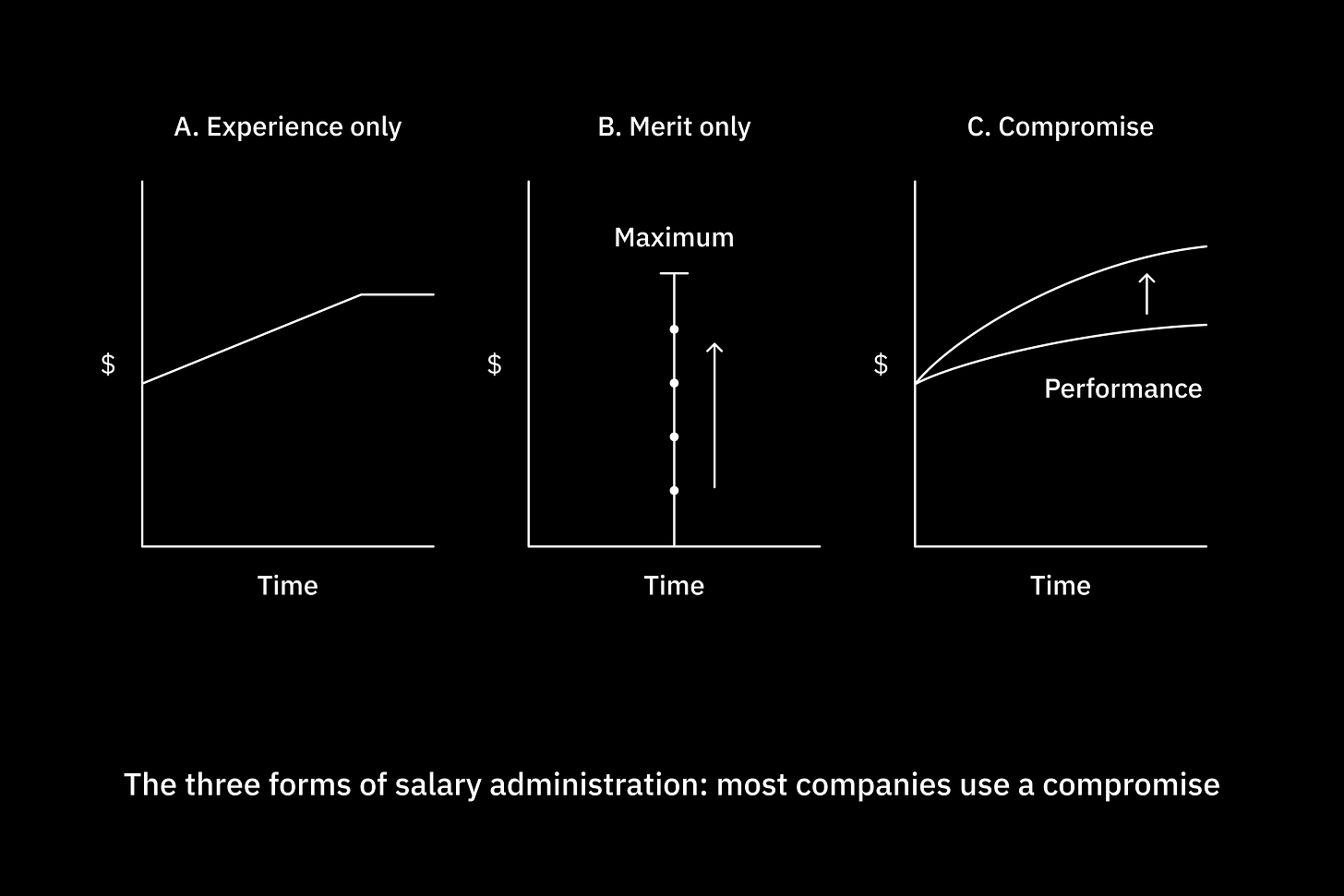

Money as a motivator

At the lower levels of Maslow’s hierarchy, money is essential. After a certain point, more money doesn’t equal more motivation.

Unless money is a measure of achievement, money at the physiological and safety stages only motivates until needs are met. Money as a measure of success can motivate without limit.

A simple test can be used to determine where someone is in Maslow's hierarchy. If the absolute sum of a raise is significant, you are working within the physiological or safety levels. If what matters is how your raise stacks up against others, you are motivated by esteem or self-actualization, money is a measure of achievement.

Once self-actualizing, money is a proxy for progress and an important feedback mechanism for performance. Outside of money, self-actualized people want to improve their performance but feedback will need to be individualized.

Work as a game

You now know how motivation can be used to elicit peak performance. Your role as a manager is to train individuals to improve their capabilities and to bring them to the point where they are self-actualizing. Once there, motivation is self-sustaining and limitless.

Money alone will not get people there. You need to endow work with sense of play and competition.

Work should be a game. Your role as a manager is that of a coach. You establish the rules of the game and give employees ways to measure their performance.

As coach, you take no personal credit for your team's success and because of that, your team trusts you. You're tough, but fair, eliciting peak performance from each person. And finally, you were probably a good player in the past. Having played well, you understand what it takes to perform.

Seeing work as a game also teaches us how to cope with failure. In any competitive sport, at least 50 percent of all games are lost. When everyone knows that from the outset, failure is seen as par for the course and not something to dwell on.

Task-relevant maturity (TRM)

As you now know, the most important task of a manager is to elicit peak performance from their team.

Assuming you now understand what motivates people, the question becomes: what is the optimum management style?

Historically, what is seen as the best management style changes based on the most popular motivational theories at the time.

In the early nineteen-hundreds, ideas about work were simple. Managers told people what to do, and if they did it, they got paid. If they didn't, they were fired.

Leadership was crisp and hierarchical with order-givers and order-takers.

In the 1950's management theory shifted toward humanism as people realized there were nicer ways to get people to work.

Finally, as behavioral science developed, theories of motivation and leadership became subjects of carefully controlled experiments.

The findings were surprising. No one approach was effective under all conditions. There is no single best management style

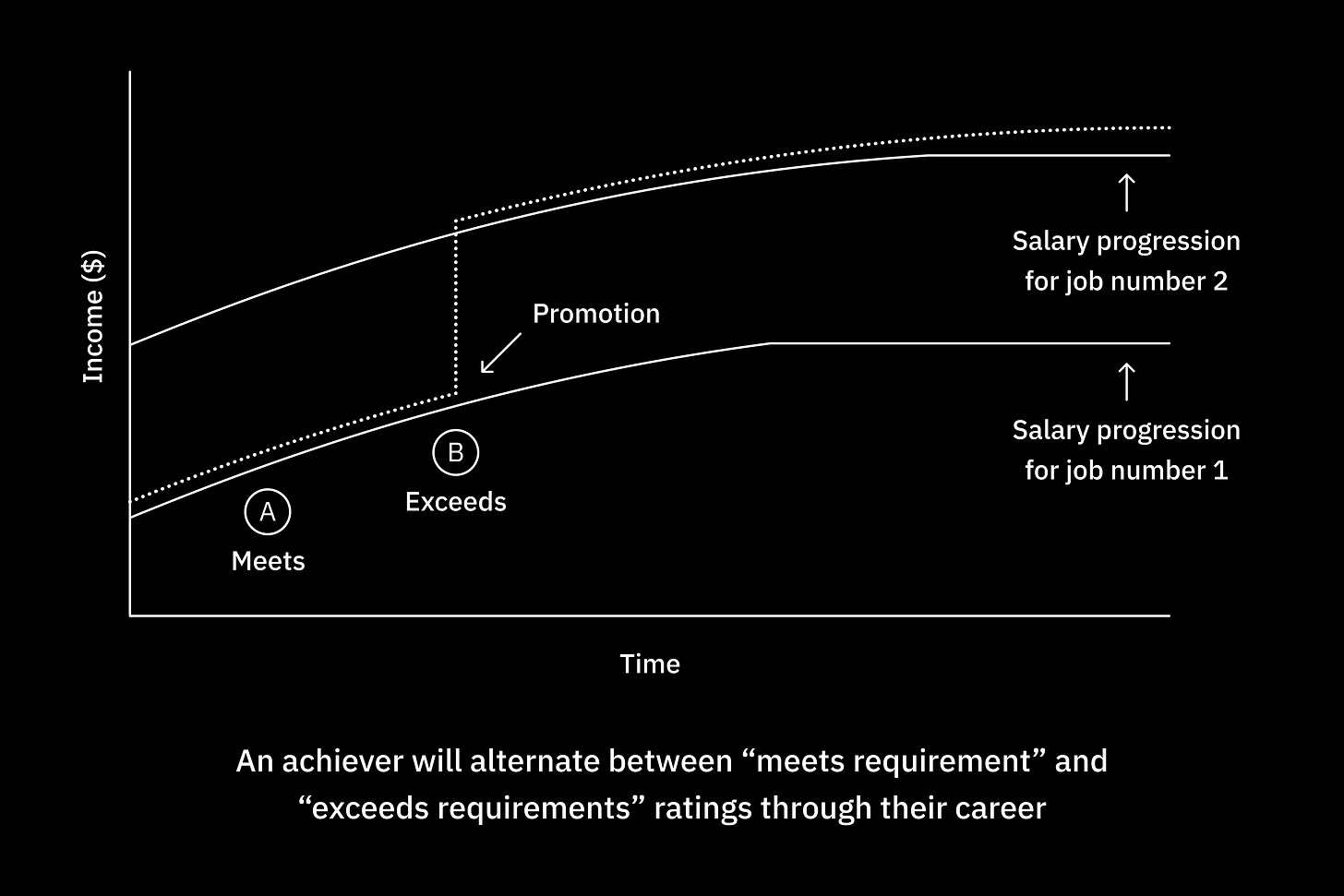

The optimum approach depends on task-relevant maturity.

What is task-relevant maturity?

Your management style should change depending on your subordinate's task-relevant maturity, which is a combination of their motivation, readiness to take on responsibility, education, training, and experience.

This is all specific to the task at hand. It's very likely that a person will have high maturity in one job but low in another. Likewise, people can have high maturity at a certain level of complexity, uncertainty, and ambiguity, but if the pace accelerates or the role changes, their maturity will drop.

When maturity is low, the most effective approach is structured, offering detailed instruction about what needs to be done, when, and how.

As maturity increases, the most effective style moves from structured to one focused on two-way communication, emotional support, and encouragement. The individual becomes more important than the task at hand.

When maturity peaks, your involvement should be minimal. Focus on ensuring the objectives your subordinate is working towards are agreed upon and correct.

But remember, you always need to monitor your team's work closely regardless of their task-relevant maturity. The presence or absence of monitoring is the difference between delegating and abdicating a task.

Avoid making a value judgment by thinking that a structured management style is less worthy than a communication-oriented one. Remember, a manager's output is the output of their team and the team's they influence. You must focus on the style that is most effective for the subordinate's maturity.

When a subordinate has low maturity, you need to teach them how you think and do things, so they can later make decisions the way you would. If you can't teach your subordinate and transmit a shared set of values, you cannot effectively delegate.

Increased maturity = increased leverage

You need to raise the task-relevant maturity of your team as fast as possible. The higher a person's task-relevant maturity, the less time it takes to manage them and once they learn your operational values, you can delegate tasks to increase your leverage.

At the highest levels, your subordinate's training is complete and motivation will likely come from self-actualization, which we know is the most potent form of motivation a manager can harness.

But remember, a person's maturity depends on their environment. When things change, maturity changes, and you must adapt your management style.

On paper, management by monitoring alone is most productive but you need to work your way up to it. Even when you get there, things can change, and you may need to revert to a what-when-how mode of management.

Why it’s hard to be a good manager

Deciding on the task-relevant maturity of each team member is hard. Even when you know, your personal preference tends to override logic and dictate your management style. We tend to opt for either a structured or a minimal approach, either fully immersed in the work of a subordinate or leaving them completely alone.

Another problem is that we often to see ourselves as more effective communicators and delegators than we really are. We also throw out suggestions that subordinates can perceive as marching orders which compounds this problem further.

A common mistake is to conflate a social relationship with an effective management style. Close relationships off the job can help create an equivalent relationship on the job, but the two shouldn't be confused.

This raises the question: Is friendship between you and a subordinate a good thing?

If a subordinate is a friend, communication-based management tends to be easy but what-when-how is harder to revert to when necessary.

You must decide what is appropriate for you. Imagine delivering a harsh performance review to a friend. If you cringe at the idea, don't make friends at work. If you're unaffected, personal relationships will strengthen work relationships.

Performance appraisal: Manager as judge and jury

Performance reviews are the single most important form of task-relevant feedback you can provide, and the truth is most managers don't do an especially good job at it.

How you assess performance, deliver the assessment, and allocate rewards like promotions, dollars, and stock options, will positively or negatively influence a report's performance for a long time. In short, performance reviews are incredibly high-leverage.

The fundamental purpose of a performance review is to improve a report's performance by focusing on their:

Skill level: To determine what skills are missing and how to remedy them; and

Motivation: To increase performance at the same skill level.

Reviews represent the most formal type of leadership. It's the only time you are mandated to act as judge and jury, you are required to make a judgement and deliver it to a fellow worker.

These two aspects of the review–assessing performance and delivering the assessment–are equally difficult, so let's look at each in more detail.

Assessing performance

The most common mistake when assessing performance is to not clearly define what you want from a direct report. If you don't know where you want to go, you can't know if you've got there.

But assessing the performance of knowledge workers is difficult. Knowledge work is fuzzy and most jobs involve activities that don't produce output in the period under review.

You must give these activities appropriate weight when assessing performance, even if you can't be 100% objective.

Using the managerial black box, we can characterize performance by output and internal measures. Output are things you can and should plot on a chart. Think completed projects, quotas, or increased yield.

Internal measures are what happen inside the black box: activities to create output for the period under review and those that set the stage for future output.

There's no formula to determine how to weigh output versus internal measures. The proper weighting could be 50/50, 90/10, or 10/90 and will shift over time.

A similar trade-off is how you weight long-term performance against short-term performance. Think about the present value: how much will the future-oriented activity pay back over time? and how much is that worth today?

You also need to consider the offset between activity and output. During the review period, output may have all, some, or nothing to do with the activities done during the same period.

You need to judge performance not just see and record what is in plain sight.

If you are reviewing a manager's performance do you judge individual performance or performance of the group under supervision? Ultimately the performance of the group, but you must determine whether they have added value and whether they are likely to increase the output of their team in the future.

Avoid the potential trap. Force yourself to assess performance, not possibility.

When deciding who to promote, understand no action communicates your values more clearly than who you promote. Every promotion creates a role model for others in your organization.

Finally, no matter how well a person has performed, find a way to suggest an improvement. Remember, the point of the review is to improve performance.

Delivering the assessment

When you are delivering a review, you want to level, listen, and leave yourself out.

Level with your report. The integrity of the system relies on honesty. And don't be surprised if praising someone is as hard as critiquing them.

The goal of the review is to transmit your thoughts to your report. The more complex the issue, the higher the probability of miscommunication. You need to listen and employ all your sensory capabilities to ensure that you are being heard. It's your responsibility to continue until you are satisfied that the review has been understood.

Leave yourself out. The review is about and for your subordinate, not you. Keep your insecurities, anxieties, guilt, and emotion out of it.

Delivering mixed reviews

Most reviews contain positive and negative assessments. Avoid delivering a list of superficial, cliche, or unrelated observations. Long lists leave your report confused and won't improve performance.

We all have a finite capacity to deal with facts, issues, and suggestions. You may want to raise seven things, but if they can only take on four, at best you'll waste your breath. At worst, you'll overwhelm them and they won't get anything from the review.

Remember, the purpose of the review is to increase performance not to share everything.

Less is often more.

Look for relationships between related issues and group them into a single item in the review.

Once you have your list, ask yourself whether your report will remember everything you have chosen. If not, delete the less important ones. What you don't include can be included in the next review.

It's preferable if reviews don't contain surprises but if you find one bring it up.

Assessing poor performers

If you are assessing a poor performer, you'll need to work through the five stages of problem-solving.

Poor performers tend to ignore their problems. You’ve made progress when they actively deny the problem rather than ignoring it.

Find facts and examples to demonstrate reality. You know you've made progress when they admit it’s a problem but maintain it's not their problem.

If they have a problem, there’s no way of resolving it if they blame others. The most significant step is when they assume responsibility, then finding the solution is relatively easy.

Your job is to get them to move through each stage, but finding the solution should be a shared task.

There are three possible outcomes, the report:

Accepts your assessment and recommended cure and commits to taking it;

Disagrees with your assessment but accepts your cure; or

Disagrees with your assessment and doesn’t commit to doing what you’ve recommended.

The first outcome is ideal, but any commitment to action is acceptable. Complicated issues don’t lend themselves to universal agreement. If your subordinate commits to change, assume they’re sincere.

If you can't get them past the blame others stage, you need to go back to the what-when-how mode of management and get their commitment to the course of action and then monitor their performance against the commitment.

Assessing top performers

While we provide poor performers with detailed feedback, the majority of reviews for high performers make little or no attempt to define what they need to improve.

If you're assessing a top performer, you must make an effort to suggest ways to improve their performance. Remember, the purpose of a review is to improve future performance.

This is backwards. You should spend more time trying to improve the performance of your best people. After all, these people account for a disproportionate share of the organization's performance. If they get better, the impact on group output is enormous.

Not only is it incredibly high leverage, it's what the best people want. There is always room to improve and top performers crave feedback.

Other thoughts and practices

Is it a good idea to ask a report to prepare some kind of a self-review before being reviewed by you? Probably not. If you need a report to give you a list of accomplishments, you haven't done your job as a manager. The act of evaluating an employee is a formal act of leadership. Don’t get nudged by self-reviews and commit to non-bias performance reviews.

Should your report evaluate your performance? This can be a good idea, if you make it clear that it’s your job to assess their performance, and their assessment of you is only advisory. Don’t pretend you and your reports are equal during performance reviews.

Should you deliver the written review before, during, or after the face-to-face discussion? Give your report the written report before the face-to-face conversation. They can read it and will be more emotionally prepared.

Preparing and delivering performance reviews is one of the hardest tasks you'll have to perform as a manager. The best way to learn to do them well is to think critically about the reviews you have received and what made them good or bad.

Interviewing potential employees, reference checks, and talking existing employees out of quitting

Interviewing potential and talking existing employees out of quitting are two of the most difficult tasks you must perform as a manager.

The purpose of interviewing is to:

Select a good performer;

Educate them about you and the company;

Determine if there is a mutual fit; and

Sell them on the job.

As we’ve learned, assessing the performance of your team is hard. Sitting down with someone for an hour to try and find out how they'll perform in a new environment is near impossible.

But you have no real choice but to perform the interview. Just realize the chance of failure is high.

You should also research past performance by checking references. The problem is you'll often be talking to a stranger. Even if they're 100% honest, what they say won't have much meaning unless you know about how the company operates, and what values it works by.

Conducting the interview

During the interview, the applicant should do 80% of the talking, but what they talk about should be your main concern.

The good news is you have a great deal of control if you are actively listening.

When you ask a question, they may go on and on until long after you've lost interest. Most people sit and listen until the end out of courtesy.

You should interrupt. Remember, you only have an hour or so. Don't waste the only asset you have to assess potential performance.

The interview is yours to control, and if you don't, you only have yourself to blame.

You'll get the most insight if you steer the discussion toward subjects you're both familiar with.

Applicants should talk about themself, their experience, what they've done, and why, as well as past decisions they would change. Just make sure the words they use mean the same thing to both of you.

Don't use tricks. The interview should be completely straightforward. Remember, candidates are potential employees. The first impression you make will stay long after you hire them, so show yourself and the environment as it really is.

The best interview questions

When writing High Output Management, Andy asked Intel's managers for the best interview questions. These are what they provided: